|

Mining waste shapes the landscape

at Guru Rosia |

In December 2003, the European Union amended a piece of its environmental legislation commonly referred to as the Seveso II Directive.

The Directive holds a long history of regulatory responses to major industrial accidents involving dangerous chemical substances. The first happened in Europe in 1976. A dense cloud of poisonous and carcinogenic dioxin vapour - a by-product of pesticide and herbicide manufacturing - was released from a reactor at a chemical plant in Seveso, Italy. To prevent similar accidents from happening in the future, the EU in 1982 passed the Directive on the Major Accident Hazards of Certain Industrial Activities, known as the Seveso Directive. In 1996, following two other major accidents, the first at Bhopal, India, in 1984, and the second at Basel, Switzerland, in 1986, the Directive on the Control of Major Accident Hazards was adopted and became known as the Seveso II Directive. It fully replaced the original Seveso Directive and brought provisions regulating chemical plants and storage facilities where dangerous substances are present in quantities above certain threshold levels. Besides responding to Europe's own environmental protection needs, Seveso II also fulfilled the obligations of the EU arising from the UNECE Convention on the Transboundary Effects of Industrial Accidents, which entered into force in 2000.

Amendments triggered by accidents

In 1999, the obligations of the Seveso II Directive become mandatory for

industry as well as for the public authorities in the fifteen EU countries.

The Directive has also been transposed into the national legislation of

twelve accession countries. The last country to adopt it was Romania, in

2003. The December 2003 amendments were again triggered by accidents: the

cyanide and heavy metals spill that polluted the Danube following a dam

burst of a tailing pond at Baia Mare in Romania in January 2000, the fireworks

accident at Enschede in the Netherlands in May 2000, and the explosion at

a fertiliser plant in Toulouse, France, in September 2001. The amendments

expanded the scope of the Seveso II Directive to include a larger number

of potentially dangerous activities and sites, i.e. processing activities

in mining, pyrotechnic and explosive manufacturing sites, and sites for

the storage of ammonium nitrate and similar fertilizers. EU member countries,

including the ten due to join the Union in May this year, are required to

implement the newly amended Seveso II by mid-2005.

Minimising risks

When proposing the amendment to Seveso II in 2001, Margot Wallström,

the EU's Environment Commissioner, said: “Even if we cannot eliminate

the risk of industrial accidents altogether in modern societies, we must

ensure that European legislation aiming to reduce such risks to a minimum

is adapted and improved”. That industrial risk is real, indeed, was

also demonstrated by the ICPDR, which following the Baia Mare accident identified

in the Danube River Basin alone over 110 industrial and mining hotspots

of medium and high priority, almost half of them in Romania.

|

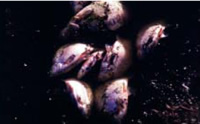

Dead fishes as a result of the

Baia Mare accident in the Danube River Basin |

Risks arising from mining activities in particular - generally associated

with altered landscape, changes in surface and groundwater regime and quality,

effects on air and soil quality, impacts on ecosystems, loss of productive

land use, and physical instability of waste facilities - need to be further

regulated. For example, even with the latest amendment, Seveso II does not

cover tailings disposal facilities that do not contain any hazardous substances

other than those naturally present in the ground, such as heavy metals.

To ensure adequate coverage of risks from such tailings disposal facilities

and to promote environmentally safe management of mining waste in general,

the European Commission is now proposing the adoption of a Mining Waste

Directive. This proposal was triggered by two major mining accidents, the

1998 accident at Aznacolar, Spain, and the already mentioned Baia Mare accident.

“As a result of the amendment of the Seveso II Directive and in particular

of the proposed directive on the management of mining waste,” says

Fotios Papoulias, of the DG Environment of the European Commission, “the

management of mining waste in Central and Eastern European countries will

definitely improve since EU standards will apply both to the operation of

mining facilities and the after-closure management of mining waste in order

to prevent or limit environmental damage resulting from day-to-day operations

or serious accidents”. According to the EU official, “this will

be achieved in particular through sound permitting and monitoring procedures,

efficient mechanisms for dealing with accidents (complementary to the Seveso

II Directive) and sufficient guarantees for restoration”.

Jürgen Wettig, of the DG Environment, adds: “The biggest problem

with this legislation is that it is reactive rather than pro-active, i.e.,

the political will to broaden the scope of a piece of legislation often

develops only after an accident has happened. This is contrary to the precautionary

principle that requires that measures be taken before an accident actually

happens. It is true that the Seveso legislation imposes burdens on the chemical

industry - an argument often used by those opposing changes in the legislation.

However, many people forget that the cost of an accident is usually much

higher than investment in prevention”.

Further information:

http://europa.eu.int/comm/environment/seveso/

http://europa.eu.int/comm/environment/waste/mining/index.htm

http://www.unece.org/env/teia

http://www.natural-resources.org/environment/BaiaMare/index.htm