Large Scale Restoration

of Channels--

Most

of the methods described above can be used in small stretches of river,

and especially in comparatively small streams, to produce local improvements

in fish populations. Most of the solutions are also of relatively low

cost. The methods described in this section are more complicated and require

a greater level of investment. The goal is not only to restore channel

diversity, but also to allow the river to develop a lateral expansion

zone that may have some of the characters of a true floodplain.

Most

of the methods described above can be used in small stretches of river,

and especially in comparatively small streams, to produce local improvements

in fish populations. Most of the solutions are also of relatively low

cost. The methods described in this section are more complicated and require

a greater level of investment. The goal is not only to restore channel

diversity, but also to allow the river to develop a lateral expansion

zone that may have some of the characters of a true floodplain.

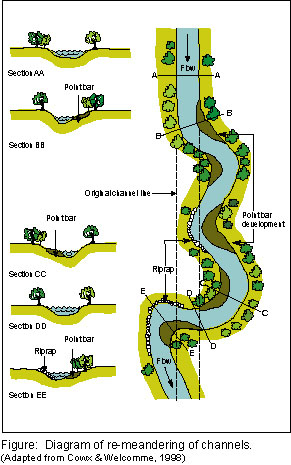

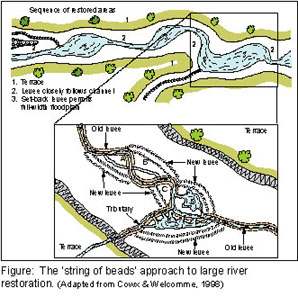

The simplest approach to the restoration of larger stretches of straight channel is to restore the meander (winding or curving) structure. In the case of river straightening, this can be done by breaking the levees that contain the channel, allowing it to return to its original river bed. More frequently, the former bed of the river has disappeared, and new channels have to be dug artificially.

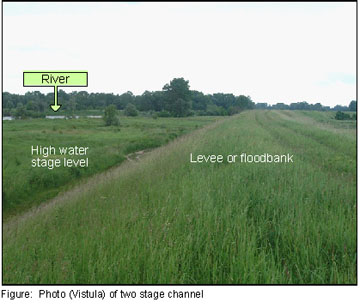

A second approach is to construct a multi-stage channel by setting back

the levee on one or both sides of the river so that there is a low flow

and a high flow channel.

|

|

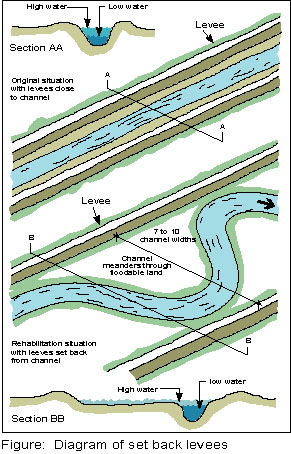

Levees can be set back even further from the main channel

allowing space in which the river can re-establish its meanders naturally.

Alternatively, engineering solutions can be used to start the river meandering

process. The space between the levees forms a floodplain in which many

of the features, such as backwaters, channels, floodplain lakes and swamps

can develop or be introduced. The plain can also be used for several purposes

including wildlife reserves, reforestation, the grazing of cattle or growing

of crops during the dry season.

As far as possible, channel diversity should be increased by reconnection

of old channels and side arms that were cut off by the old levee structures

close to the river.

Restoration of the Floodplain--

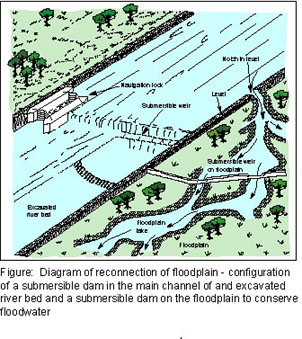

The main objective in reconnecting the floodplain

is to restore lateral connectivity, especially to former floodplain water

bodies that have become isolated from the channel. Restoring lateral connectivity

is important for improving wetland ecosystem function, restoration of

aquatic plant communities and waterfowl habitat, and restoring migration

pathways for fish and other aquatic animals. This usually involves breaking

the levee and actively reconnecting the pool, wetland or channel to the

main channel of the river. A new flood control structure (levee) may have

to be built behind the reconnected waterbody. Sluice gates or submersible

weirs may control flow into and out of the waterbody. The waterbody may

be connected at the upstream and downstream end or at the downstream end

only. The way in which the waterbody is connected affects its ecological

characteristics and the types of vegetation, invertebrates, birds and

fish that eventually colonize the restored habitat.

In addition to reconnection of existing but old floodplain features, new

features can be made by connecting borrow pits, and sand and gravel extraction

sites near to the river. Leaving such sites in a suitable condition for

connection to the river can be a condition of the water extraction license

issued to the developer.

It is equally important to conserve and restore the floodplain itself,

especially where it is (or was) forested. Floodplain forest and mangroves

have high social and economic value to people, and also high environmental

value to the aquatic organisms that depend on them for habitat. They also

contribute to the maintenance of biodiversity of many species of animals

including fish, some of which have become highly dependent on forest products

such as fruit for feeding. The practice of clearing flooded forest and

converting this habitat to rice culture is a serious problem in the Mekong

Basin, particularly along the fringes of the Great Lake in Cambodia. This

loss of habitat has serious repercussions on biodiversity. Therefore,

projects designed to reforest cleared areas are a valuable component of

rehabilitation programmes.

In areas where the floodplain has been separated from the main channel

for a long time, flooding may not occur because the channel bed has been

eroded downwards to a point where the bankfull state is never exceeded.

Two solutions have been used to overcome this difficulty:

submersible dams can be installed across the river raising the level at a particular point from which it can be deflected onto the floodplain;

lowering the level of the floodplain by scraping off the surface layers of soil. In either case, it may be necessary to install submersible weirs across the floodplain to direct the water and retain it as long as possible.

It is clear that the total conservation

of the river system in a pristine state, or even in its current condition,

is unrealistic. The needs for economic and social development will continue

to place demands on the river and its landscape that are not wholly compatible

with the interests of many of the plant and animal species that inhabit

natural floodplains. This means that specific, but limited areas should

be set aside as reserves along the river for the conservation of aquatic

fauna, so long as the linkages between them are preserved. In other rivers,

the idea that the structure of the river and floodplain needs to be restored

or protected in specific areas along the river is termed the 'string of

beads' approach.

It is, however, not enough to simply create reserve areas. These must

be selected according to their significance to species, or groups of species,

as breeding, nursery, feeding and refuge sites. In addition, the pathways

between the various sites must be kept clear so that fish and other aquatic

organisms can move freely between them.

|

|