Caspian Sea >> Background

English | Russian

The Caspian Sea is the biggest enclosed body of water on Earth, having

an even larger area than that of the American Great Lakes or that of Lake

Victoria in East Africa. It is situated where the South-Eastern Europe meets the

Asian continent, between latitudes 47.07’N and 36.33N and longitudes 45.43 E and

54.20E. It is approximately 1,030 km long and its width ranges from 435 km to a

minimum of 196 km. It has no connection to the world’s oceans and its surface

level at the moment is around –26.5 m below MSL. At this level, its total

coastline is some 7,000 km in length and its surface area is 386,400 km2.

The water volume of the lake is about 78,700 km3.

The Caspian Sea is the biggest enclosed body of water on Earth, having

an even larger area than that of the American Great Lakes or that of Lake

Victoria in East Africa. It is situated where the South-Eastern Europe meets the

Asian continent, between latitudes 47.07’N and 36.33N and longitudes 45.43 E and

54.20E. It is approximately 1,030 km long and its width ranges from 435 km to a

minimum of 196 km. It has no connection to the world’s oceans and its surface

level at the moment is around –26.5 m below MSL. At this level, its total

coastline is some 7,000 km in length and its surface area is 386,400 km2.

The water volume of the lake is about 78,700 km3.

The water of the Caspian Sea is slightly saline; if

we compare the Caspian water with oceanic water, it contains 3 times less

salt.

So, why is the Caspian water saline? The Caspian Sea

is a remnant of the ancient ocean, named Tethis, or more exactly of its

Paratethis bay. About 50 – 60 million years ago the Tetis ocean connected the

Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans. However, due to gradual shift of continental

platforms it lost its connection with the Pacific ocean and later on with the

Atlantic Ocean. As a result, the water body became isolated from the world

ocean. Therefore, the salinity of the Caspian Sea can be attributed to its

origin from an ancient ocean.

Why is the water of the Caspian Sea 3 times less

salty than the waters of the world ocean? During hot and dry climatic periods

the low precipitation quantity caused the Paratethis to dry up and divide into

separate water bodies. It is due to these conditions of reduced water and

isolation that the water in the Paratethis became slightly saline. During cool

and wet climatic periods, great levels of precipitations caused the water bodies

at the Paratethis to over flow and again connect the many water bodies,

thus becoming less saline. The melting of ice fields was another cause for

the reduction of salinity within the Paratethis waters as the ice diluted the

salt contents.

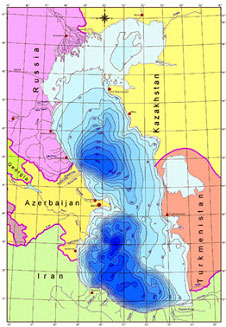

The Caspian can be considered as divided into three

parts, the northern, middle and southern parts. The border between the northern

and middle parts runs along the edge of the North Caspian shelf (the Mangyshlak

threshold), between Chechen Island (near the Terrace River mouth) and Cape

Tiub-Karagan (at Fort Shevchenko). The border between the middle and southern

parts runs from the Apsheron threshold connecting Zhiloi Island in the west to

Cape Kuuli in the east (north of Turkmenbashi).

The northern part covers about 25% of the

total surface area, while the middle and southern parts cover around 37% each.

However, the water volume in the northern part accounts for a mere 0.5%, while

the volume in the middle part make up 33.9%, and in the southern part 65.6% of

Caspian waters. These volumes are a reflection of the bathymetry of the Caspian.

The northern part is very shallow, with average depths of less than 5m. In the

middle part, the main feature is the Derbent Depression with depths of over

500m. The southern part includes the South Caspian Depression with its deepest

point being 1025m below the surface.

Approximately 130 large and small rivers flow into the Caspian, nearly

all of which flow into the north or west coasts. The largest of these is the

Volga River that drains an area of 1,400,000 sq. km and runs into the northern

part of the Caspian. Over 90% of the inflowing freshwater is supplied by the 5

largest rivers: Volga – 241 km3, Kura – 13 km3, Terek – 8.5 km3, Ural – 8.1 km3

and Sulak 4 km3. The Iranian rivers and the smaller streams on the western

shores supply the rest, since there are no permanent inflows on the eastern

side.

Approximately 130 large and small rivers flow into the Caspian, nearly

all of which flow into the north or west coasts. The largest of these is the

Volga River that drains an area of 1,400,000 sq. km and runs into the northern

part of the Caspian. Over 90% of the inflowing freshwater is supplied by the 5

largest rivers: Volga – 241 km3, Kura – 13 km3, Terek – 8.5 km3, Ural – 8.1 km3

and Sulak 4 km3. The Iranian rivers and the smaller streams on the western

shores supply the rest, since there are no permanent inflows on the eastern

side.

Apart from the extensive shallows of the northern

part, the other two physical features that characterize the Caspian are the

Volga and the Kara Bogaz Gol gulf.

The Volga Delta is situated in the Prikaspiisk

lowlands covering around 10,000 km2 and the delta has a width of about 200 km. A

feature of the delta region are the so-called Baer knolls which are hillocks,

between 3m and 20m in height, formed by the action of onshore winds on the river

sediments. These sediments are discharged into the delta at a rate of 8 million

tones per year. Numerous small lakes can be found between the knolls and there

is a complex system of channels with many islets. The Volga-Caspian shipping

canal traverses the delta and is dredged to maintain a depth of no less than

2m.

The Kara-Bogaz Gol is situated on the eastern coast

of the Caspian Sea and bites deep into the hinterland. It can be considered to

be the largest lagoon in the world and is separated from the sea by sand bars.

Until 1980, Kara-Bogaz-Gol was one of the significant evaporative sinks for the

Caspian Sea. Historical outflow to the Kara-Bogaz-Gol between 1900-1979 averaged

15 km3 per year (nearly 4 cm). At the beginning of the 20th century, when the

sea level was much higher, the strait between the Caspian Sea and Kara-Bogaz-Gol

allowed a flow of 30 km3 of water per year to the smaller basin. During

subsequent years, the flow consistently decreased due to reduced fluvial inflow

and sea-level fall. In an attempt to retard any further drop in sea level, a

solid dam was constructed across the strait in March of 1980. This dam

effectively isolated Kara-Bogaz-Gol from the Caspian basin, thus preventing

further outflow of water to the bay. This closure caused more than 40 km3 of

water to be retained within the Caspian Sea and contributed an additional 11 cm

to the rising water levels. As a result, the average yearly rate of sea-level

rise increased by 2.5-2.7 cm. In September 1984, a spillway was opened in the

dam to permit some discharge of water to the Gulf. In June 1992, the dam was

completely removed. This episode reflects the difficulty of anticipating natural

variations in the hydrologic cycle and creating engineering works to counter

this natural variability effectively.

The Caspian region lies in the center of the

Palaearctic zoogeographical realm and is comprised of two major biomes – cold,

continental deserts and semi-deserts in the north and east and, warmer mixed

mountain and highland systems with complex zonation in the southwest and south.

There is also a small area around the Volga Delta in the west, where temperate

grasslands can be found. The range of climatic conditions that prevail around

the Caspian Sea have lead to a significant degree of biological diversity. This

is further enhanced by the existence of extensive wetland systems such as the

deltas of the Volga, the Ural and the Kura rivers and the hypersaline Kara Bogaz

Gol.

The biodiversity of the Caspian aquatic environment

derived from the long history of the existence of the sea and its isolation,

allowing ample time for speciation. The number of endemic aquatic taxa, which is

over 400, is very impressive. There are 115 species of fish, of which a number

are anadromous and migrate from the Caspian up the rivers to spawn. The best

known of these are the seven species and subspecies of sturgeon, which have been

a valuable economic resource for over a century. Furthermore, the Caspian seal

is one of only two freshwater seal species that occur worldwide; the other is

found in Lake Baikal.

Recently, hybridization has occurred between the sturgeon from the

Black Sea and those in the Caspian. This phenomenon can be explained due to the

connection which is now possible via the Don-Volga Canal. While the precise

effects this hybridization may have on the Caspian environment are currently

hard to evaluate, the potential loss of diversity among the sturgeon species is

a cause of serious concern.

Recently, hybridization has occurred between the sturgeon from the

Black Sea and those in the Caspian. This phenomenon can be explained due to the

connection which is now possible via the Don-Volga Canal. While the precise

effects this hybridization may have on the Caspian environment are currently

hard to evaluate, the potential loss of diversity among the sturgeon species is

a cause of serious concern.

Coastal wetlands, including temporary and permanent

shallow pans, many of which are saline, attract a variety of birdlife. Birds are

prolific throughout the year, in and around the Caspian, and their numbers swell

enormously during the migration seasons when many birds patronize the extensive

deltas, shallows and other wetlands. It is at these times that

ecologically-motivated visitors could be guided into carefully selected vantage

points and allowed to experience the beauty and the bounty of protected

ecological resources. Such eco-tourism, carefully planned and managed, has

tremendous potential both as an income earner and as an excellent mechanism to

educate and inform the interested public, whether they are local or from

overseas.

The Caspian Sea region is a major economic asset. It

has large oil and gas reserves that are only now beginning to be fully

developed. Oil reserves for the entire Caspian region are estimated at 18 – 35

billion barrel, comparable to those in the United States (22 billion) and the

North Sea (17 billion barrels). Natural Gas reserves are even larger, accounting

for almost two-thirds of the hydrocarbons reserves. The region’s possible oil

reserves yield another billions of barrels what is part of allure of the Caspian

region. (Energy Information Administration, US)

Undeniably, the Caspian environment is of great

interest for many people the world over: Scientists and technical specialists

have been challenged by the Caspian unique nature as the largest land-locked

body of water on earth, the petroleum industry has been tapping its oil and gas

wealth for decades, gourmets have extolled the virtues of its caviar and those

concerned with ecological resources have recognized its valued biological

diversity.

©2009 CaspEcoProject Management and Coordination Unit

7-th floor, Kazhydromet Building, Orynbor st., Astana, 010000, Republic of Kazakhstan,

Tel. No.: (+7 7172) 798317; 798318; 798320, 798307, E-Mail: MSGP.MEG@undp.org