The nature of the Baltic Sea

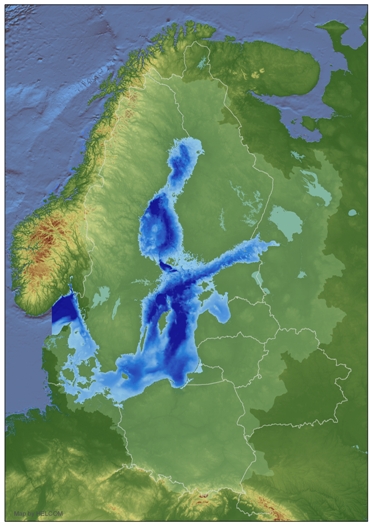

The Baltic Sea is a small sea on a global scale, but as one of the world's largest bodies of brackish water it is ecologically unique. Due to its special geographical, climatological, and oceanographic characteristics, the Baltic Sea is highly sensitive to the environmental impacts of human activities in its sea area or in its catchment area, which is home to over 85 million people.

The Baltic Sea is a small sea on a global scale, but as one of the world's largest bodies of brackish water it is ecologically unique. Due to its special geographical, climatological, and oceanographic characteristics, the Baltic Sea is highly sensitive to the environmental impacts of human activities in its sea area or in its catchment area, which is home to over 85 million people.

What makes the Baltic so sensitive?

An almost enclosed sea

The Baltic Sea is only connected to the world’s oceans by the narrow and shallow waters of the Sound and the Belt Sea. This limits the exchange of water with the North Sea, and means that the same water remains in the Baltic for up to 30 years – along with all the organic and inorganic matter it contains.

The Baltic Sea consists of a series of sub-basins, which are mostly separated by shallow sills. These basins each have their own water exchange characteristics.

Runoff enters the shallow Baltic Sea from a large catchment area

At an average depth of just 53 metres, the Baltic Sea is much shallower than most of the world’s seas. It contains 21,547 km³ of water and every year rivers bring about 2% of this volume of water into the sea as runoff. The Baltic Sea’s catchment area is almost four times larger than the sea itself.

Brackish water

The brackish water of the Baltic Sea is a mixture of sea water from the North Sea and fresh water from rivers and rainfall. The salinity of its surface waters varies from around 20 psu (≈parts per thousand) in the Kattegat to 1–2 psu in the northernmost Bothnian Bay and the easternmost Gulf of Finland, compared to 35 psu in the open oceans.

A stratified sea

Salinity levels also vary with depth, increasing from the surface down to the seafloor. Saltier water flowing in through the Sound and the Belt Sea does not mix easily with the less dense water already in the Baltic, and tends to sink down into deeper basins. At the same time, the less saline surface water flows out of the Baltic. The boundary between these two water masses, known as the halocline, consists of a layer of water where salinity levels change rapidly. In the Baltic Proper and Gulf of Finland, for instance, the halocline lies at a depth of around 60–80 m. Like a lid, the halocline limits the vertical mixing of water. This means that the oxygen content of the deep basins may decline due to biological and chemical oxygen consumption. The Baltic Proper is replenished by oxygen-rich saltwater flowing in from the North Sea along the sea floor.

The Gulf of Bothnia, separated by a shallow sill from the Baltic proper, has low bottom water salinity and, hence, a very weak or absent halocline. In summer a thermocline – a distinct layer of water where the temperature changes rapidly – divides surface waters into two layers: a wind-mixed surface layer down to a depth of 10–25 m, and a deeper, denser and colder layer extending down to the sea-bed or the halocline. Such temperature stratification ends as surface waters cool in the autumn.

Limited biodiversity

Compared to other aquatic ecosystems, only relatively few animal and plant species live in the brackish ecosystems of the Baltic Sea – although this limited biodiversity does include a unique mix of marine and freshwater species adapted to the brackish conditions, as well as a few true brackishwater species. Where salinity levels are low, in the Baltic’s northern and eastern waters, fewer marine species can thrive, and habitats are dominated by freshwater species, especially in estuaries and coastal waters.

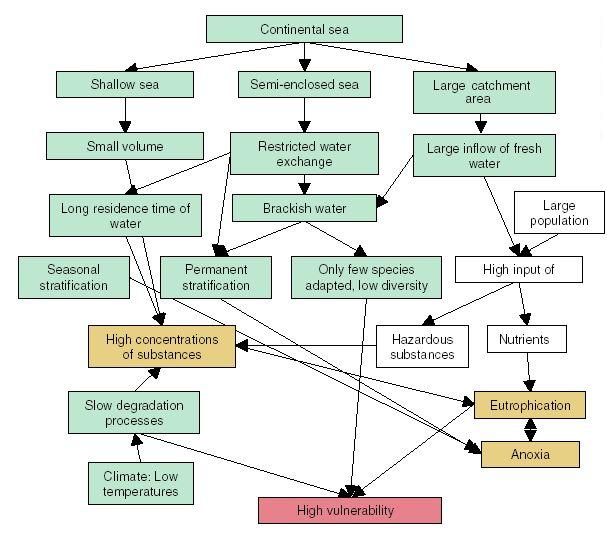

Figure 1. Specific features and processes which make the Baltic Sea sensitive (green - natural characteristics, white - human impacts, yellow - harmful effects)