Insects .

Insects abound in fresh waters: they dominate the communities of streams

and small rivers, and are responsible for much of the flow of energy in

these ecosystems (see Section 7) serving as a major for a range of fishes,

amphibians and birds. Some  families

of insects are aquatic throughout their lives, while for others the main

aquatic stage is the larva (the opposite – terrestrial larvae and aquatic

adults – is extremely rare). The adults usually have wings, and these

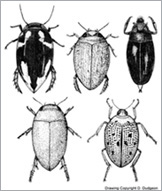

remain functional in most species (of dytiscid Coleoptera, for example)

that have aquatic adults. Colonization of new habitats, or recolonization

of those that have dried out, has almost certainly been the evolutionary

advantage that has favoured the retention of functional wings in adult

aquatic insects. It may also account for their success in fresh waters

and other habitats.

families

of insects are aquatic throughout their lives, while for others the main

aquatic stage is the larva (the opposite – terrestrial larvae and aquatic

adults – is extremely rare). The adults usually have wings, and these

remain functional in most species (of dytiscid Coleoptera, for example)

that have aquatic adults. Colonization of new habitats, or recolonization

of those that have dried out, has almost certainly been the evolutionary

advantage that has favoured the retention of functional wings in adult

aquatic insects. It may also account for their success in fresh waters

and other habitats.

All insects have three main body parts: the head, thorax, and abdomen.

Three pairs of jointed legs and two pairs of wings are located on the

thorax, while the abdomen may have lateral gills or filaments, prolegs

('false legs' that are short and not jointed), and/or anal gills and 'tails'

or cerci. Some insects develop gradually through the life cycle with the

juvenile coming to resemble the adult form more and more as it nears maximum

size. These are more ancient orders of insects. They consist of fewer

species than orders that have distinct, and very different, larval and

adult stages separated by a pupal stage when the insect metamorphosis

takes place.

Insect adaptations: aquatic respiration

Respiration under water is a problem for any animal which, like an insect,

has evolved from terrestrial ancestors. On land, respiration is accomplished

by way of a network of air-filled tubes or trachea through which gaseous

oxygen is distributed to various parts of the body. A series of openings

or spiracles (which can be closed by  muscles)

connect the tracheal system to the surrounding air. Insects have evolved

a number of solutions to the problem of aquatic respiration; they fall

into two groups. Some species come to the water surface and have at least

one pair of functional spiracles with which they breathe atmospheric oxygen.

Some adult Coleoptera and Heteroptera carry a bubble underwater that is

used as an air store.

muscles)

connect the tracheal system to the surrounding air. Insects have evolved

a number of solutions to the problem of aquatic respiration; they fall

into two groups. Some species come to the water surface and have at least

one pair of functional spiracles with which they breathe atmospheric oxygen.

Some adult Coleoptera and Heteroptera carry a bubble underwater that is

used as an air store.

In the second group of species, the spiracular system is closed and oxygen

is obtained through the body surface. Most s pecies

carrying out respiration in this way require well-aerated water, although

some Diptera (Chironomidae) can survive oxygen-poor conditions because

their 'blood' contains haemoglobin. Many insects have thin-walled, often

leaf-like projections from the body that contain tracheae. Others possess

filamentous bunches or tuft-like outgrowths of the tracheal system. These

structures are variously termed gills (in Ephemeroptera , Plecoptera,

Trichoptera and Lepidoptera), filaments (in Megaloptera) or lamellae (in

Zygoptera). All seem to have a respiratory function. The ability to ventilate

the gills varies in different groups: some Ephemeroptera beat the gills

rhythmically; most Trichoptera undulate the abdomen drawing water over

the gills. However, many insects cannot ventilate their gills effectively

and so are confined to running water where the current ensures a continuous

supply of oxygen. Insects with functional spiracles breathe atmospheric

oxygen and can occupy a wide range of habitats; they dominate in floodplain

areas or places where flow and dissolved oxygen may be limited.

pecies

carrying out respiration in this way require well-aerated water, although

some Diptera (Chironomidae) can survive oxygen-poor conditions because

their 'blood' contains haemoglobin. Many insects have thin-walled, often

leaf-like projections from the body that contain tracheae. Others possess

filamentous bunches or tuft-like outgrowths of the tracheal system. These

structures are variously termed gills (in Ephemeroptera , Plecoptera,

Trichoptera and Lepidoptera), filaments (in Megaloptera) or lamellae (in

Zygoptera). All seem to have a respiratory function. The ability to ventilate

the gills varies in different groups: some Ephemeroptera beat the gills

rhythmically; most Trichoptera undulate the abdomen drawing water over

the gills. However, many insects cannot ventilate their gills effectively

and so are confined to running water where the current ensures a continuous

supply of oxygen. Insects with functional spiracles breathe atmospheric

oxygen and can occupy a wide range of habitats; they dominate in floodplain

areas or places where flow and dissolved oxygen may be limited.

Insect adaptations: dealing with current

Many insects that live on the bottom of streams and rivers (i.e., they

are benthic species) have flattened bodies, enabling them to  avoid

high current speeds by living in the slow-moving boundary layer of water

that exists immediately above the streambed. While it is almost certainly

the case that flattening is an adaptation for avoiding current in some

Ephemeroptera (e.g.,: Heptageniidae), in others it may have evolved to

allow them to fit into crevices among cobbles, and this may reflect

avoid

high current speeds by living in the slow-moving boundary layer of water

that exists immediately above the streambed. While it is almost certainly

the case that flattening is an adaptation for avoiding current in some

Ephemeroptera (e.g.,: Heptageniidae), in others it may have evolved to

allow them to fit into crevices among cobbles, and this may reflect  a

need for concealment from predators. Thus a flattened shape may be associated

with living on top of stones, or living among and underneath them. Streamlining

to reduce drag is less common than flattening, but is seen in many baetid

Ephemeroptera that have fish-like body shapes. Hydraulic suckers that

exert negative pressure are rare in stream insects but have evolved in

the dipteran family Belpharoceridae that is specialised for life in mountain

torrents. However, many species with flattened bodies that live in fast

current torrents have bodies modified to appear sucker-like. The body

margins make close contact with the rocks and, as well as increasing frictional

resistance to flow, this will prevent the current flowing under the insect

and lifting it up. Psephenidae (Coleoptera) larvae that have flat, coin-like

bodies are an example of this adaptation.

a

need for concealment from predators. Thus a flattened shape may be associated

with living on top of stones, or living among and underneath them. Streamlining

to reduce drag is less common than flattening, but is seen in many baetid

Ephemeroptera that have fish-like body shapes. Hydraulic suckers that

exert negative pressure are rare in stream insects but have evolved in

the dipteran family Belpharoceridae that is specialised for life in mountain

torrents. However, many species with flattened bodies that live in fast

current torrents have bodies modified to appear sucker-like. The body

margins make close contact with the rocks and, as well as increasing frictional

resistance to flow, this will prevent the current flowing under the insect

and lifting it up. Psephenidae (Coleoptera) larvae that have flat, coin-like

bodies are an example of this adaptation.

In many insects, a flattened shape is accompanied by well-developed strong

claws on the tips of the legs to provide a good grip on the substratum.

Claws and/or hooks are seen in other species also, and occur on both the

thoracic legs and the abdominal prolegs of Trichoptera, Megaloptera and

Gryrinidae (Coleoptera). Ephemeroptera larvae that live in fast current

tend to have shorter, thicker and more toothed claws on the legs, when

compared to  the

thin delicate claws of those dwelling in standing water. Simuliidae (Diptera)

larvae spin a mat of silk that is stuck to the rock and then attach themselves

to it by a circle of hooks on the tip of the abdomen. Like some Diptera,

Trichoptera produce silk using the salivary glands. This is used as a

material for building portable cases of sand, small stones, and leaf or

twig fragments. Stone cases can serve as ballast, and are common (or contain

larger stones) in species found in flowing water. Other Trichoptera (e.g.,

Hydropsychidae) build fixed shelters that are associated with a silk capture

net used to filter the passing water. This habit of building shelters

or tubes, as occurs also in Chironomidae (Diptera), protects the occupants

from exposure to the force of the current (and enemies). Giller and Malmqvist

(1998: Chapter 5) give a more detailed account of these and other adaptations

to life in running water.

the

thin delicate claws of those dwelling in standing water. Simuliidae (Diptera)

larvae spin a mat of silk that is stuck to the rock and then attach themselves

to it by a circle of hooks on the tip of the abdomen. Like some Diptera,

Trichoptera produce silk using the salivary glands. This is used as a

material for building portable cases of sand, small stones, and leaf or

twig fragments. Stone cases can serve as ballast, and are common (or contain

larger stones) in species found in flowing water. Other Trichoptera (e.g.,

Hydropsychidae) build fixed shelters that are associated with a silk capture

net used to filter the passing water. This habit of building shelters

or tubes, as occurs also in Chironomidae (Diptera), protects the occupants

from exposure to the force of the current (and enemies). Giller and Malmqvist

(1998: Chapter 5) give a more detailed account of these and other adaptations

to life in running water.

Ephemeroptera

The

order Ephemeroptera (mayflies) comprises over 2,000 species worldwide.

They occur in a variety of freshwater habitats but are most diverse in

small rivers; very few species live in standing water. All Ephemeroptera

have aquatic larvae and short-lived terrestrial adults that do not feed.

Although the adults are rather uniform in structure, larvae exhibit a

variety of morphologies: the body of active swimmers is streamlined, while

species sprawling on or clinging to rocks are flattened; many burrowing

Ephemeroptera have cylindrical bodies with tusks on the head and broad

forelimbs for digging. Respiration is by leaf-like abdominal gills or

gill tufts, and Ephemeroptera larvae can be recognised by their possession

of abdominal gills and two or three 'tails' (i.e., cerci or caudal filaments)

at the end of the abdomen. Most Ephemeroptera feed on periphytic algae

(or biofilm) and fine organic particles (although a tiny minority are

filter feeders or predators). For this reason, and because they are generally

abundant, Ephemeroptera play an important role in freshwater food chains.

The

order Ephemeroptera (mayflies) comprises over 2,000 species worldwide.

They occur in a variety of freshwater habitats but are most diverse in

small rivers; very few species live in standing water. All Ephemeroptera

have aquatic larvae and short-lived terrestrial adults that do not feed.

Although the adults are rather uniform in structure, larvae exhibit a

variety of morphologies: the body of active swimmers is streamlined, while

species sprawling on or clinging to rocks are flattened; many burrowing

Ephemeroptera have cylindrical bodies with tusks on the head and broad

forelimbs for digging. Respiration is by leaf-like abdominal gills or

gill tufts, and Ephemeroptera larvae can be recognised by their possession

of abdominal gills and two or three 'tails' (i.e., cerci or caudal filaments)

at the end of the abdomen. Most Ephemeroptera feed on periphytic algae

(or biofilm) and fine organic particles (although a tiny minority are

filter feeders or predators). For this reason, and because they are generally

abundant, Ephemeroptera play an important role in freshwater food chains.

The most species-rich families of Ephemeroptera in stony streams and small

rivers are Baetidae, Heptageniidae and Leptophlebiidae; Ephemerellidae

and, in areas of quiet water, Caenidae are of secondary importance. In

larger rivers, burrowing or wood-boring Ephemeroptera in the Ephemeridae,

Polymitarcyidae and Potamanthidae occur, although a few species of caenids

and specialised baetids (mainly Cloeon) may be present.

Odonata

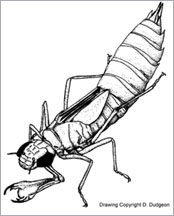

Adult stages of the Odonata (collectively termed dragonflies) are conspicuous

insects that are often large and colourful, although the larvae are less

familiar. The order consists of about 5,500 species and is most diverse

in tropical latitudes. It is made up of two suborders: the Zygoptera (damselflies)

and Anisoptera (dragonflies). Adult Zygoptera are slender insects, with

fore- and hindwings that are similar in general appearance and held above

the body when perching. Their larvae have three (occasionally two) external

gills situated at the tip of the elongated abdomen, and can be in the

form of sacs, flat blades, or leaf-like structures. Adult Anisoptera –

or dragonflies – are relatively stout (and usually larger) strong-flying

insects, with fore- and hindwings that differ somewhat in shape that are

held flat when the insect perches. Their larvae have internal gills within

the rectum, and are relatively squat-bodied with a short, broad abdomen.

Water projected from the anus by contraction of the rectal muscles can

cause dragonfly larvae to shoot through the water as though they were

jet-propelled.

|

|

All odonate larvae are predators,

and prey are captured with the aid of a highly modified and elongate,

grasping labium or 'lower lip'. It can be projected forward rapidly to

grasp prey whereupon it is retracted bringing the prey within reach of

the jaws. When not in use, the labium is folded flat beneath the head.

The adults are predators also.  Larvae

will eat almost any type of aquatic prey, whether vertebrate or invertebrate,

the only limitation being what they are able to catch. Cannibalism is

common.

Larvae

will eat almost any type of aquatic prey, whether vertebrate or invertebrate,

the only limitation being what they are able to catch. Cannibalism is

common.

Many families of Zygoptera are riverine specialists, and forested hillstreams

are especially rich in species. Chlorocyphidae, Calopterygidae and Euphaeidae

are typical of upland rivers. Coenagrionidae are associated with both

standing and flowing water and, like the Platycnemidae, are characteristic

of lowland rivers and floodplains where the larvae are often found among

aquatic macrophytes. The majority of Anisoptera species occurs in slow-flowing

or standing water, but the diverse Gomphidae includes a large number of

species confined to rivers where larvae may burrow in sand and mud waiting

to ambush prey. Macromiidae are also mainly confined to running water.

A few genera of Aeshnidae and Libellulidae are restricted to streams,

but these two families are more diverse in ponds, marshes and floodplain

pools. Odonate adults are often colourful, and males may guard territories

that they patrol constantly. Species such as Pantala flavescens (Libellulidae)

have migratory adults, that breed in temporary pools.

Plecoptera

Plecoptera

(stoneflies) are diverse in temperate latitudes, but most tropical species

are confined to the upper, stony reaches of rivers where the temperature

is relatively cool and constant, and oxygen is readily available. Larvae

have gill tufts on the thorax and a pair of 'tails' (called cerci) at

the end of the abdomen. Adults are poor fliers and are seldom encountered.

Although there are around 1,800 species in 15 families worldwide, only

three families are of importance in Asian rivers. The Perlidae (mainly

subfamily Neoperlinae) includes the majority of species; all are predators

on other insects and some may be quite large. The Nemouridae are small

Plecoptera that eat decaying plant material, and the Leuctridae contains

a few species that burrow into stream sediments where they feed on fine

organic matter.

Plecoptera

(stoneflies) are diverse in temperate latitudes, but most tropical species

are confined to the upper, stony reaches of rivers where the temperature

is relatively cool and constant, and oxygen is readily available. Larvae

have gill tufts on the thorax and a pair of 'tails' (called cerci) at

the end of the abdomen. Adults are poor fliers and are seldom encountered.

Although there are around 1,800 species in 15 families worldwide, only

three families are of importance in Asian rivers. The Perlidae (mainly

subfamily Neoperlinae) includes the majority of species; all are predators

on other insects and some may be quite large. The Nemouridae are small

Plecoptera that eat decaying plant material, and the Leuctridae contains

a few species that burrow into stream sediments where they feed on fine

organic matter.

Heteroptera

The Heteroptera (aquatic bugs) includes insects that utilise aquatic habitats

as larvae and adults. The fall into two major ecological groups: one is

semiaquatic because they live on the surface of the water; they belong

to the suborder Gerromorpha and are carnivores that forage for insects

that have  drowned

or become trapped in the surface film. The second group – suborder

Nepomorpha – is a mixture of families that live under water; many

are free swimming. This means that, in general, they are confined to pools

or river reaches where the current is not too swift to prevent swimming,

although some Naucoridae (Aphelocheirus) live on the bed of fast-flowing

stony streams.

drowned

or become trapped in the surface film. The second group – suborder

Nepomorpha – is a mixture of families that live under water; many

are free swimming. This means that, in general, they are confined to pools

or river reaches where the current is not too swift to prevent swimming,

although some Naucoridae (Aphelocheirus) live on the bed of fast-flowing

stony streams.

The combined total number of aquatic and semiaquatic species of Heteroptera

approaches 4,000. Tropical Asia is particularly rich in species, and Gerromorpha

are found in almost all water bodies – even on the surface of swift streams

and around waterfalls. Heteroptera are characterised by forewings that

are hard and leathery – at least in the anterior portion. In addition,

they all have syringe-like mouthparts. In the majority of species, feeding

involves the injection of enzymes (and sometimes venom) into prey followed

by digestion of tissue that is sucked out and swallowed. The forelegs

of most families are raptorial; i.e., modified for grasping prey. Only

one family (the Corixidae) has become modified for herbivorous feeding

with mouthparts are adapted for rasping, not sucking.

The Gerromorpha is made up of the Gerridae – the large and conspicuous

Water striders or Water skaters, which have greatly elongated second and

third pairs of legs – and the relatively tiny Veliidae. The Nepomorpha

contains a greater variety of insects, including those that live suspended

in the water column (the Notonectidae or 'Backswimmers'), crawl or swim

over the river bed (Naucoridae and Corixidae), are associated with aquatic

macrophytes (Belostomatidae and some Nepidae), or sprawl on the bottom

mud (other Nepidae). Some are large: Gigantomera (Gerridae) has

hind legs almost 100 mm long while Lethocerus (Belostomatidae),

which can reach 80 mm in length, can be cooked and eaten.