Trichoptera

The Trichoptera is a diverse order of freshwater insects. The global species

total is not known but there are over 600 genera. Tropical Asia is disproportionately

rich in  Trichoptera

compared to the rest of the world, and is estimated to support as many

as 50,000 species. Some genera (e.g., Chimarra: Philopotamidae)

may contain 500 Southeast Asian species! Trichoptera can be divided broadly

into species that are free-living, and may or may not live within a portable

case, and those that live within fixed shelters; most species in the second

group spin a net with which they filter the passing water for food. The

adults of all species are moth-like creatures with hair-covered wings;

a few (Macrostemum: Hydropsychidae) are brightly coloured but most

are dull and inconspicuous.

Trichoptera

compared to the rest of the world, and is estimated to support as many

as 50,000 species. Some genera (e.g., Chimarra: Philopotamidae)

may contain 500 Southeast Asian species! Trichoptera can be divided broadly

into species that are free-living, and may or may not live within a portable

case, and those that live within fixed shelters; most species in the second

group spin a net with which they filter the passing water for food. The

adults of all species are moth-like creatures with hair-covered wings;

a few (Macrostemum: Hydropsychidae) are brightly coloured but most

are dull and inconspicuous.

Because they are such a diverse group, Trichoptera occupy a range of freshwater

habitats; the majority are found in rivers although some case-building

species (mainly Leptoceridae) are confined to standing water. Feeding

habits are likewise varied. Filter-feeding by means of silk nets occurs

in the species-rich Philopotamidae and Hydropsychidae, but larvae of some

case-building families (e.g., Leptoceridae) sieve food particles from

the current with the aid of bristles on the legs. The architecture of

nets spun by filter-feeders varies among species: some use coarse mesh

with large pores, others produce fine mesh with minute pores. This results

in a difference among species in the types of food captured and eaten.

It also has the effect that some species live in faster currents than

others: fine-meshed nets function best in slow currents, whereas coarse-meshed

nets are effective in swift currents that transport relatively large particles.

The use of different foods and microhabitats contributes to a downstream

replacement (or longitudinal zonation) of species in some Trichoptera

and is seen in the Hydropsychidae, which are generally the most abundant

family of Trichoptera in Asian Rivers.

|

The case-making Calamoceratidae and Lepidostomatidae (plus some Leptoceridae)

eat dead leaves while the Rhyacophilidae, Polycentropididae and Ecnomidae

are predators. Some Hydropsychidae supplement their diet by eating insects

accidentally swept into their capture net by the current, while polycentropodids

use their silken net to trap or entangle prey. The Glossosomatidae, Xiphocentronidae,

Psychomyiidae and Helicopsychidae are grazers, although the dependence

upon algae in some families is not well established. Psychomyiidae and

Xiphocentronidae eat considerable quantities of fine organic particles;

the Dipseudopsidae live on this material entirely. The habit of piercing

plant cells (usually filamentous algae) and sucking out their contents

is confined to the Hydroptilidae. Although not exhaustive, this list indicates

the ecological diversity and success of Trichoptera that must, at least

in part, be attributable to the use of silk in net-spinning and case/shelter-building.

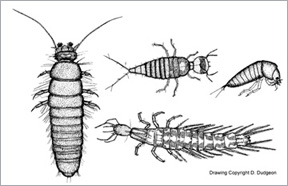

Coleoptera

In terms of number of described species, the Coleoptera is the largest

animal order. Although they are diverse in tropical Asian streams, ecological

research on aquatic Coleoptera – or  water

beetles – has been hampered by a lack of information on immature

stages, and most larvae cannot be identified to species or even genus.

Some families (e.g., Psephenidae) have terrestrial adults, but the adults

and larvae of the species-rich families (i.e., Elmidae, Dytiscidae and

Hydrophilidae) are aquatic. Elmidae adults and larvae occur together in

the same microhabitat, but this is not always the case for other Coleoptera

so it can be difficult to associate a particular larval type with an adult.

Beetle larvae vary in body form, and although most are elongate with short

legs, Psephenidae are coin-like and flattened. In small rivers, the Coleoptera

fauna is dominated by Elmidae and Psephenidae, with a few representatives

of Eulichadidae and Gyrinidae (adults of which live on the water surface

and are called Whirligig beetles). Hydrophilidae and Scirtidae include

species that live in fast and slow-flowing water, as well as marshy areas,

whereas the Dytiscidae (the most species rich family) occurs mostly in

pools or slow moving water and among aquatic plants. Food habits vary

also: Psephenidae and some Elmidae graze periphyton; Scirtidae eat fine

particles of organic matter; and the Dytiscidae, Gyrinidae and Hydrophilidae

(larvae only) are predators. The Eulichadidae and some Elmidae appear

to feed on dead wood.

water

beetles – has been hampered by a lack of information on immature

stages, and most larvae cannot be identified to species or even genus.

Some families (e.g., Psephenidae) have terrestrial adults, but the adults

and larvae of the species-rich families (i.e., Elmidae, Dytiscidae and

Hydrophilidae) are aquatic. Elmidae adults and larvae occur together in

the same microhabitat, but this is not always the case for other Coleoptera

so it can be difficult to associate a particular larval type with an adult.

Beetle larvae vary in body form, and although most are elongate with short

legs, Psephenidae are coin-like and flattened. In small rivers, the Coleoptera

fauna is dominated by Elmidae and Psephenidae, with a few representatives

of Eulichadidae and Gyrinidae (adults of which live on the water surface

and are called Whirligig beetles). Hydrophilidae and Scirtidae include

species that live in fast and slow-flowing water, as well as marshy areas,

whereas the Dytiscidae (the most species rich family) occurs mostly in

pools or slow moving water and among aquatic plants. Food habits vary

also: Psephenidae and some Elmidae graze periphyton; Scirtidae eat fine

particles of organic matter; and the Dytiscidae, Gyrinidae and Hydrophilidae

(larvae only) are predators. The Eulichadidae and some Elmidae appear

to feed on dead wood.

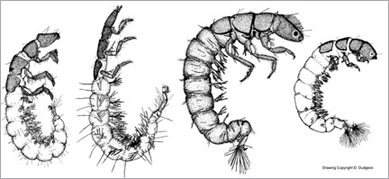

Diptera

Adult

Diptera are notorious ectoparasites of humans and livestock, and many

transmit disease-causing parasites. Mosquitoes (Anopheles: Culicidae)

carry malaria throughout the tropics and blackflies (Simuliidae) transmit

nematode and protozoan parasites. Apart from the relatively few species

with medical importance, the Diptera (='true' flies) have received scant

attention from river ecologists in Asia. This is despite the fact that

they are one of the most diverse orders of aquatic insects. A common approach

has been to identify the aquatic larvae to the level of family or subfamily

and treat all members of a group as being ecologically equivalent. The

main reason for this state of affairs is that most Diptera larvae have

elongate bodies and all lack segmented legs; they do not possess conspicuous

external gills or other features, and even a head capsule is lacking in

certain groups. This has meant that species identification depends upon

examination of the terrestrial adults, and these are rarely associated

with the aquatic larvae.

Adult

Diptera are notorious ectoparasites of humans and livestock, and many

transmit disease-causing parasites. Mosquitoes (Anopheles: Culicidae)

carry malaria throughout the tropics and blackflies (Simuliidae) transmit

nematode and protozoan parasites. Apart from the relatively few species

with medical importance, the Diptera (='true' flies) have received scant

attention from river ecologists in Asia. This is despite the fact that

they are one of the most diverse orders of aquatic insects. A common approach

has been to identify the aquatic larvae to the level of family or subfamily

and treat all members of a group as being ecologically equivalent. The

main reason for this state of affairs is that most Diptera larvae have

elongate bodies and all lack segmented legs; they do not possess conspicuous

external gills or other features, and even a head capsule is lacking in

certain groups. This has meant that species identification depends upon

examination of the terrestrial adults, and these are rarely associated

with the aquatic larvae.

There are two dipteran suborders: Nematocera and Brachycera. Larvae of

the latter lack a head capsule and the body is often pale and maggot-like.

We know little about the ecology Brachycera in Asian rivers, but they

are not abundant in most habitats. The Nematocera are, by far, the most

diverse aquatic Diptera and, within this suborder, the Chironomidae (or

non-biting midges) numbering at least 20,000 species are arguably the

richest and most abundant family of stream macroinvertebrates. Chironomids

occur in all freshwater habitats, especially where there is some water

movement, but they are tolerant of a wide array of conditions, including

low oxygen and organic pollution. Because most species are small (<10

mm long), their abundance is often underestimated in ecological studies.

Some chironomids graze algae, others filter or gather fine organic particles

from their surroundings, or use a combination of these feeding modes;

some even eat wood. One subfamily (the Tanypodinae) feeds on other chironomids,

and the Chironomidae is an important prey item in the diet of almost all

other aquatic insectivores.

Other

important families of aquatic Nematocera are the Simuliidae, Culicidae,

and to a lesser degree, the Tipulidae. The Blephariceridae are of minor

ecological importance as algal grazers in mountain torrents. Simuliidae

larvae are filter feeders and capture minute particles (mainly smaller

than five microns) from the current using fan-like structures on the head;

they are restricted to fast-flowing water in small stony streams or the

mainstream of larger rivers. The adult females of some Simuliidae (a minority)

require a meal of vertebrate blood before they can lay eggs. Culicid larvae

are generally found in floodplain pools, backwaters, or areas protected

from the current. They filter or gather algae and fine particles of organic

matter with their mouthparts; one genus (Toxorhynchites) is predatory

(often cannibalistic). Adult females of many species are blood feeders.

The Tipulidae includes species that spend their entire life cycle on land

as well as species with aquatic larvae and, for a dipteran, these larvae

can be large (up to 40 mm long). Some tipulids are predators, while others

eat decaying plant material; at least one genus (Antocha) grazes

periphyton.

Other

important families of aquatic Nematocera are the Simuliidae, Culicidae,

and to a lesser degree, the Tipulidae. The Blephariceridae are of minor

ecological importance as algal grazers in mountain torrents. Simuliidae

larvae are filter feeders and capture minute particles (mainly smaller

than five microns) from the current using fan-like structures on the head;

they are restricted to fast-flowing water in small stony streams or the

mainstream of larger rivers. The adult females of some Simuliidae (a minority)

require a meal of vertebrate blood before they can lay eggs. Culicid larvae

are generally found in floodplain pools, backwaters, or areas protected

from the current. They filter or gather algae and fine particles of organic

matter with their mouthparts; one genus (Toxorhynchites) is predatory

(often cannibalistic). Adult females of many species are blood feeders.

The Tipulidae includes species that spend their entire life cycle on land

as well as species with aquatic larvae and, for a dipteran, these larvae

can be large (up to 40 mm long). Some tipulids are predators, while others

eat decaying plant material; at least one genus (Antocha) grazes

periphyton.

Other aquatic insects

Two other aquatic insect orders warrant attention. The order Megaloptera

(i.e., fishflies) is represented mainly by the Corydalidae in Asia. The

aquatic larvae occur in stony rivers, and crawl onto land to metamorphose

into the terrestrial adult. Corydalid larvae are predaceous with well-developed

strong mandibles. The abdomen has a series of lateral filaments, which

may have a respiratory function, and larger species have gill tufts at

the bases of these filaments.

|

|

The Lepidoptera is a huge order of terrestrial insects that includes

some species with aquatic larvae; all are in the family Pyralidae. They

have a caterpillar-like body shape (sometimes flattened) and are easily

separated from other aquatic insects by the presence of four pairs of

prolegs on the underside of the abdomen; these are used to aid locomotion.

Lepidoptera larvae produce silk: species in fast-flowing rivers live on

top of stones and cover themselves by a protective silk tent. They graze

periphyton. Those that occur in slower flows are usually associated with

aquatic macrophytes, and use silk to make a portable protective case out

of leaf fragments. Herbivorous larvae of terrestrial Lepidoptera may attack

emergent macrophytes, and rice is subject to pest species that bore into

the stems.