|

When ships navigate from place to place, they sometimes carry tiny uninvited passengers – plants and animals that stick to their hulls or are carried in ballast water. These organisms often find new homes along the ship's route and may flourish in huge numbers thanks to a lack of predators. Sometimes, people also intentionally introduce new species hoping to improve fisheries. The shores and waters of the Black Sea support large numbers of “introduced” species from other parts of the world. Some of these are truly unwelcome guests. What can be done to prevent them from arriving? |

Introduction

The unintentional and intentional transport of animals from place to place is not a new problem. Throughout human history, people have introduced domesticated animals into non-native environments as part of farming. Do you know where chickens, turkeys and cows originally came from? Sometimes though, people have made serious mistakes such as introducing rabbits to Australia without understanding that there were no predators able to control their numbers. The rabbits have seriously damaged the natural environment and destroyed huge areas of crops. Conditions on early ships were often rather poor and rats found places to hide on board. They were spread to many islands where they caused extinctions of native birds and animals. Unbeknown to the sailors however, their ships were also transporting many marine species that clung to the hulls.

A pause for thought

|

How do you prevent rats from jumping off a ship? They will not normally jump into the water. Think of some of the ways they could get off a ship and how we can prevent them from doing so. |

|

It is only in the last hundred years or so that we have become aware of the spread of marine alien species by ships. Ancient ships were slow, allowing only a few hardy species such as barnacles, worms and algae to cross the oceans. Modern ships travel from place to place very quickly. The biggest change however, is that many modern cargo vessels transport ballast water. What is ballast water? Some ships such as oil tankers and bulk carriers (of raw materials from mining or agriculture) are like huge empty boxes when they are not loaded. They float so high out of the water that their propellers are at the sea surface and the ship cannot navigate safely and economically. This is why they take seawater into their tanks (special tanks on modern ships) from the place where they unloaded their cargoes; enough water to enable efficient and safe operation of the ship. When they arrive to the place where they load up a new cargo, they pump the water back into the sea … but this may be in another continent! Imagine the number of animals and their eggs and larvae, tiny plants, bacteria and even smaller viruses that can be transported in a 100,000-ton tanker!

Factfile

|

It is estimated that about 10 billion tonnes of ballast water are transferred globally each year (International Maritime Organisation, 2001). |

And now to the Black Sea

The Black Sea 's low salinity and fertile coastal waters resemble the conditions in many of the estuaries and coastal seas where major ports are located in other parts of the world. This makes it particularly vulnerable to invasions.

|

Try to make a list of some of the places around the world that may be linked to the Black Sea by trade with oil tankers and large bulk carriers. |

|

There have been over one hundred known invasions of exotic species to the Black Sea . Some were quickly accommodated into the ecosystem and other caused huge problems. Two case studies help to understand the issues involved:

Case study 1 – a giant sea-snail!

In 1946, a Russian scientist, E.I. Drapkin discovered a beautiful new pink sea-snail, Rapana thomasiana in Novorossiiysk Bay . The snail had arrived mysteriously from the Sea of Japan . Soon, large numbers of the animals began to appear. Rapana is a voracious carnivore that feeds on oysters, mussels and other bivalves (bivalves are molluscs with two hinged shells). It rapidly destroyed the native oyster and mussel beds in the Eastern Black Sea and seriously depleted those on the Bulgarian and Romanian side. In the 1980s a lucrative new industry emerged; to fish for Rapana and export it back to Japan and Korea where it is considered a great delicacy! This sounds like a perfect solution to the problem. The first Rapana fisheries were by diving and hand collecting with little or damage to life around it. Then heavy dredging equipment started to be employed. This destroys everything in its path and can turn the Rapana headache into an ecological nightmare.

|

Case study 2 – an alien rainbow comb jelly!

Some time in the early 1980s, a cargo of ballast water brought from the East Coast of North America was discharged into the Black Sea . With the water a beautiful translucid rainbow-like tubular organism found its way to the Black Sea . The new arrival was Mnemiopsis leidyi , commonly know as a comb jelly. This 10cm swimming creature lives by filtering small marine animals from the sea and can produce over 1000 eggs per day, enabling it to spread very quickly. With no natural enemies in the Black Sea , it is hardly surprising that a huge population developed with as much as 1.2 Kg of animals in a single cubic metre in 1990! At the same time, the presence of such a huge and hungry population resulted in a complete collapse of anchovy fisheries; anchovy larvae were probably part of Mnemiopsis's diet.

There was a major debate on whether or not Mnemiopsis could be controlled (see Moral Maze below). One of its few natural predators is an even larger comb jelly called Beroe. In 1997 Beroe also arrived in the Black Sea , probably in ballast water. By that time, Mnemiopsis numbers had already begun to decline but the presence of Beroe seems to have reduced number still further. Both Mnemiopsis and Beroe will now probably become permanent residents of the Black Sea ecosystem. |

Controlling the Invasions.

Keeping rats from jumping off a ship is not easy but imagine how difficult it is to prevent marine organisms from being transported from place to place! Ship owners have struggled for centuries to keep what they describe as ‘fouling' organisms from the hulls of ships. These organisms collect on the bottom of a ship turning it into a mobile underwater garden and slowing it down, increasing maintenance and operational costs. The invention of toxic ‘anti-fouling' paints reduced the problem but recent formulations with organic tin compounds have also seriously polluted some coastal areas and killed vulnerable species. Some of these compounds are now banned, forcing ship-owners to seek safer products or to return to the copper-based products used for over a century.

ith ballast water, the situation is more complicated. The amount of water transported is vast and, despite efforts to develop new water treatment technology, treating it all on board to remove all living organisms does not appear to be realistic. The International Maritime Organisation, a United Nations body based in London , is asking ship-owners to try a simpler approach. Ships should pump out the ballast water (originally taken from the harbour of departure) in mid-ocean and gradually replace it with cleaner ocean water that is not so likely to contain undesirable species. When they arrive at the port of destination, they will be discharging water with mid-ocean species that are less able to thrive in coastal waters. This is not a perfect solution, but it may help to stop a serious and growing world problem; a problem that may have permanently changed the Black Sea 's ecosystems.

|

Ship-owners are currently not legally obliged to exchange ballast waters in mid ocean. Think of some good arguments to persuade them to do this and write a letter to the owner of an oil tanker that travels between America and the Black Sea asking him to ensure that his ship follows the guidelines. |

|

The moral maze – what do you think?

|

|

When the invasion of Mnemiopsis occurred, scientists tried to find a solution. The amount of Mnemiopsis was greater than the entire world annual capture of fish so physical removal of the animals was impossible. On the other hand, some scientists suggested introducing one or more new species of fish that might be able to consume the invaders. The problem was that nobody really knew what would happen to the ecosystem with the additional new species. Would human intervention make the situation better or cause a new problem? Some scientists were frustrated that no action was taken, others were outraged that fellow scientists could tinker with nature. Eventually no action was taken; people felt that the uncertainty was too great. Nature took its course, with a little help from another invader (see Case Study 2 above).

There are many cases like this at present. Some companies for example, are developing genetically modified plants that they claim will improve our future agriculture. Other experts consider the risk of altering natural systems as being too great. There is no unequivocal evidence for or against. What do we believe in and how do we chose? Do we need to establish a code of environmental ethics to help us make such decisions? |

|

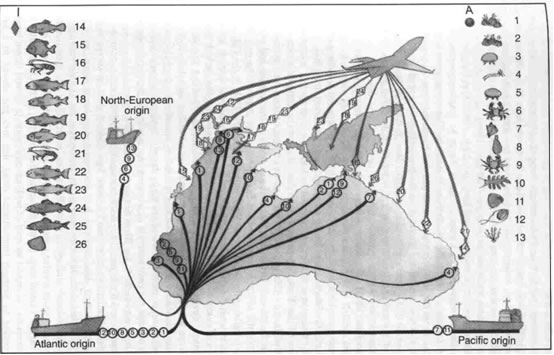

Illustration of invasive species

Here is a diagram showing some species carried to the Black Sea by ships or introduced intentionally (shown with an aeroplane). This is from the work of Academician Yuvenaly Zaitsev from Odessa in Ukraine , one of the world's leading experts in the field. |