Population Development of Baltic Bird Species:

Population Development of Baltic Bird Species:

Great Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis)

|

||||

Key message

During the 19th century the Great Cormorant was exterminated as a breeding bird in several Baltic countries. The persecution continued during the 20th century, and in the early 1960s the European breeding population of the continental subspecies sinensis had declined to 4 000 breeding pairs (bp) only, of which Germany and Poland hosted more than the half.

As a result of protection measures, breeding pair numbers started to increase during the 1970s. During the 1980s, the Cormorant started to expand its range towards the northern and eastern parts of the Baltic. Currently, the species is present in the whole Baltic Sea area, including the northern parts of the Gulf of Bothnia.

The breeding population of the Cormorant has stabilized in the south-western Baltic (Denmark and the northern Federal States of Germany - Schleswig-Holstein and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania) after a decade of exponential growth, but breeding populations are still growing in the central and north-eastern parts of the Baltic Sea.

The highest population density is found around the highly eutrophic estuaries of the southern Baltic (Odra-, Vistula-, and Curonian lagoon).

Results and assessments

Relevance of the indicator for describing developments in the environment

The Great Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis) is a representative of species which have been nearly extinct due to persecution in the 19th and first half of the 20th century. Its current development shows the recovery after the establishment of effective protection measures. The recovery takes place both in population size and in breeding range.

Furthermore, the Cormorant is a species which benefits from eutrophication.

Policy relevance and policy references

The Cormorant is protected by the provisions of the EU Bird Directive (79/409/EEC), which are implemented by the Member States into national law. This means, the legal protection status of the Cormorant is similar in all Baltic Sea states except of Russia. The species is not listed in Annex I of the Bird Directive, i.e., there is no obligation for the Member States to establish Special Protected Areas (SPA). It is also not listed in Annex II of the Bird Directive, which means the national states are not allowed to give the Cormorant an open hunting season, i.e. the species cannot be a game bird. However, according to Article 9 (1) of the EU Bird Directive, under certain conditions the Member States may allow derogations from the protection provisions of the Directive. Since the Cormorant is considered to cause damages to fish stocks and fisheries, several Member States make use of Article 9 (1) and allow derogations with the aim “to prevent serious damage to crops, livestock, forests, fisheries and water”. The activities permitted by the responsible authorities include destruction of nests, oiling of eggs, and shooting. Furthermore, illegal actions against Cormorants are also reported from several countries.

Despite the possibility of derogations from the protection provisions, national as well as European fishery and angler associations strongly demand a management of the Cormorant population with the aim to reduce the population size. These demands resulted in a non-legislative resolution of the European Parliament, adopted on December 4, 2008, on “the application of a European cormorant management plan to minimise the increasing impact of cormorants on fish stocks, fishing and aquaculture.”

This resolution calls the Commission to “submit a cormorant population management plan in several stages, seeking to integrate cormorant populations into the environment as developed and cultivated by man in the long term without jeopardising the objectives of the Wild Birds Directive and Natura 2000 as regards fish species and marine and freshwater ecosystems. MEPs (Members of the European Parliament) urge the Commission, in the interests of greater legal certainty and uniform interpretation, to provide without delay a clear definition of the term ‘serious damage’ as used in Article 9(1)(a), third indent, of the Wild Birds Directive (The Wild Birds Directive (79/409/EEC) of 2 April 1979). The Commission should also produce more generalised guidance on the nature of the derogations allowed under Article 9 (1) of the Wild Birds Directive, including further clarification of the terminology where any ambiguity may exist.”

Furthermore, the MEPs suggest that, “by means of systematic monitoring of cormorant populations supported by the EU and the Member States, a reliable, generally recognised and annually updated database should be drawn up on the development, size and geographical distribution of cormorant populations in Europe. They call on the Commission to put out to tender, and finance, a scientific project aimed at supplying an estimation model for the size and structure of the total cormorant population on the basis of currently available data on breeding population, fertility and mortality. The Commission and the Member States are called upon to foster in an appropriate manner the creation of suitable conditions for bilateral and multilateral scientific and administrative exchanges, both within the EU and with third countries.”

(http://www.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/FindByProcnum.do?lang=en&procnum=INI/2008/2177).

In its response to the EP Resolution of 4 December 2008, the Commission recognises the need for co-ordinated action but does not consider that an EU-wide management plan would be an appropriate measure to address this problem. Under the Birds Directive there is no legally binding mechanism for an EU-wide management plan. Furthermore, there is no consensus between Member States on the type of action to take, or on the need and value of managing Cormorant populations at a pan-European scale. The Commission considers that it is not proportionate to argue for action at EU level to solve problems of a regional scale. Moreover, simply reducing the population will not necessarily reduce the numbers of Cormorants around the most attractive feeding sites or the impact on those fisheries and fish stocks. A combination of local control and mitigation measures has probably more chances of success than a general reduction of the population.

The Commission is also in favour of ensuring better scientific data and making available objective and updated information that could be widely accepted by all stakeholders regarding the populations and the biology of the Cormorants across the EU and their impact on fisheries. With this purpose in mind, the Commission is planning to establish a platform for exchange and dissemination of technical information in particular on mitigation, non-lethal and lethal measures, social and economical issues and data on Cormorant populations. This will be an opportunity to bring together relevant experts, officials and stakeholders to identify the best way forward. It will be useful to promote regional cooperation among neighbouring countries concerned by this issue. In this context, a first consultation meeting on the interaction between Cormorants and fisheries was held in Brussels on March 2009 (http://circa.europa.eu/Public/irc/env/wild_birds/library?l=/cormorants/cormorants_31-03-2009&vm=detailed&sb=Title).

The next steps envisaged by the Commission comprise:

The development of a guidance document on Article 9 of the Birds Directive in relation to Cormorants, addressing issues such as “serious damage” as well as indicating what actions would be acceptable and compatible with the Directive;

The dissemination of “Best Practice” on solutions to reduce the impact of Cormorants on fisheries;

The establishment of a technical platform by the Commission for exchange of information across the EU;

The support to a methodology and mechanism for collecting population statistics that is reliable and not controversial.

Since the Baltic Sea area hosts a very large proportion of the European Cormorant population and since all Baltic Sea states except of Russia are Member States of the European Union, all activities and actions taken on EU level are directly relevant to HELCOM.

Provisional conservation targets

Actions against the Cormorant with the aim to reduce damages caused to fisheries or impacts on threatened fish species as well as incidental killing in fishing gear should not affect the range and favourable conservation status of the species.

Assessment

Cormorant Population Development in the Baltic Sea Area

During the 19th century the Great Cormorant was exterminated as a breeding bird in several Baltic countries. Persecution continued during the 20th century. The European breeding population of the continental subspecies sinensis was small throughout the first half of the 20th century. The species was successful in re-colonising Denmark in 1938 and Sweden in 1948 (Bregnballe & Gregersen 1995, Engström 2001). In the early 1960s, Germany and Poland hosted more than half of the entire European breeding population estimated at that time at c. 4 000 bp (Bregnballe 1996).

As a result of protection measures, breeding pair numbers began to increase during the 1970s (van Eerden & Gregersen 1994). By 1981, numbers in the Baltic Sea area had reached approximately 6 500 bp, and in 1991 the population was already about 51 000 bp. At the same time, an expansion to more eastern and northern breeding areas took place. In Estonia, the Cormorant started to breed in 1983, in Lithuania in 1989, on Gotland 1992, and in Finland in 1996 (Žydelis et al. 2002, SYKE 2007, V. Lilleleht, pers. comm.). The range expansion even reached the northern part of the Bothnian Bay, where a colony was established in 2000. This northernmost Baltic colony of the Cormorant grew to 220 bp in 2008 (Lehikoinen 2006; SYKE 2008).

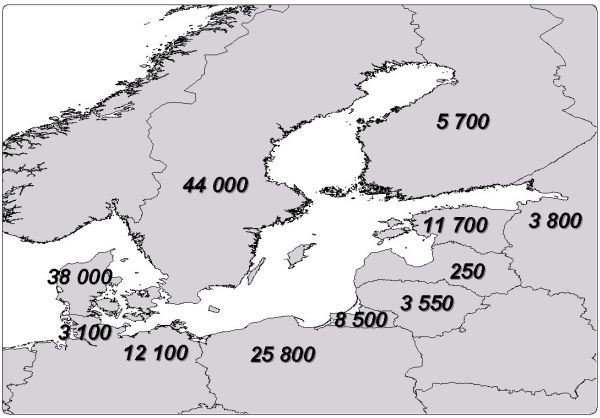

In 2006, the total number of breeding pairs of Great Cormorants in the Baltic Sea riparian states amounted to about 157 000 in 410 colonies, with almost 80 % of the birds breeding in Denmark, Germany, Poland and Sweden[1] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Breeding pair numbers of the Great Cormorant in the Baltic Sea area 2006. Data from the European Cormorant Count 2006 (Wetlands International Cormorant Research Group and the "Extended network and conflict analysis project" of COST-INTERCAFE).

An annual complete Cormorant surveillance is established in some of the Baltic countries (e.g., Denmark, Germany, Estonia and Finland), but not in all (e.g., not in Sweden and Poland). However, the available data include representative samples from all parts of the Baltic Sea, giving a clear picture for the development in the different regions.

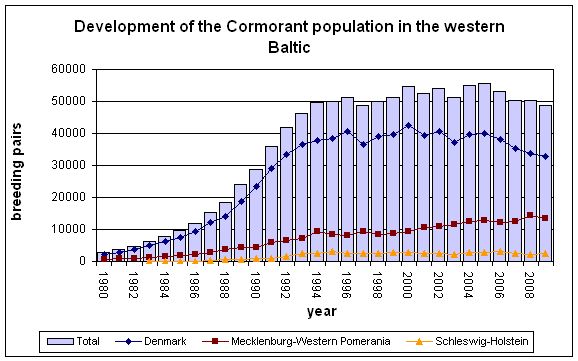

In the south-western part of the Baltic (Denmark, Schleswig-Holstein and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania), the breeding pair numbers increased rapidly during the 1980s until the mid-1990s. However, since about 1994 the population has been fairly stable on a level of about 50 000 bp (Figure 2). Although breeding numbers have been almost constant in the south-western part of the Baltic during the last 15 years, shifts in distribution have been observed. In south-east Denmark, for instance, from 1993 to 2008 the population declined from c. 13 000 bp to c. 7 000 bp, whereas in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania an increase was observed. In Schleswig-Holstein, numbers have increased along the North Sea coast but have declined along the Baltic Sea coast (Koop & Kieckbusch 2007).

Figure 2: Population development of the Cormorant in the south-western Baltic 1980-2009.

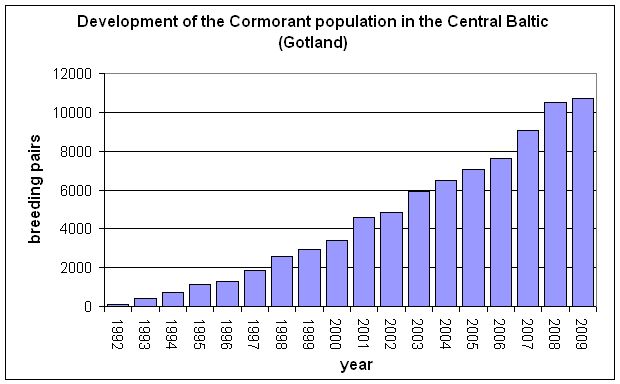

The development on Gotland is an example of how numbers have developed in the central Baltic. The Cormorant began breeding at Gotland in 1992. The population has continued to increase since then (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Number of breeding pairs of Cormorants on the island Gotland, Sweden. Data from K. Larsson, M. & B. Hjernqvist, and S. Hedgren.

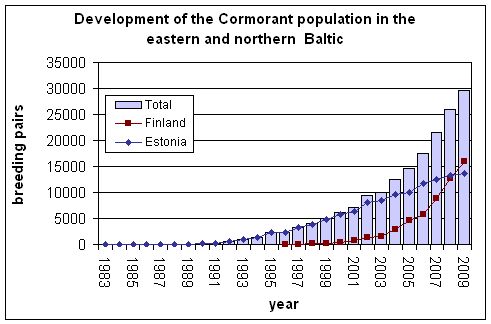

The development in eastern and northern parts of the Baltic is here illustrated using Estonia and Finland as examples. The overall trend is very similar to that observed in the central Baltic. The first breeding of Cormorants in Estonia was recorded in 1983, but the population remained small (< 100 bp) until the end of the 1980s. At the beginning of the 1990s, breeding numbers started to increase rapidly and numbers still continue to grow, though the annual growth rate has been low since 2003. In Finland, the first breeding was recorded in 1996 and the population grew to about 16 000 bp in 2009.

Figure 4: Population development of the Cormorant in the eastern and northern Baltic (Estonia and Finland). Data from SYKE (2008, 2009), Lilleleht (2008), and Evironmental Board of Estonia (2009, pers. com).

Regional distribution of breeding sites

The vast majority of the Cormorants breeding in the Baltic are nesting in colonies located near to the coast, and almost all large colonies >1 000 bp are found in coastal areas. The breeding sites are quite often islets where the birds build their nests on the ground or on trees.

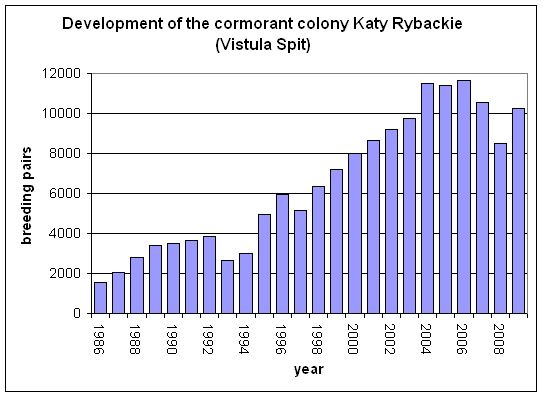

The highest concentration of Cormorants is found around the highly eutrophic estuaries of the large rivers of the southern Baltic: Vistula Lagoon (11 500 bp in 2006 in a colony on Vistula Spit, Poland; Figure 5), Odra lagoon (10 750 bp in 2006 in five colonies in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Poland), and Curonian Lagoon (11 300 bp in 2006 in two colonies on the Lithuanian and the Kaliningrad side of the lagoon). The largest colonies are: Katy Rybackie (at the Vistula Spit, Poland; 11 637 bp in 2006), a colony on the south coast of the Curonian lagoon (Kaliningrad region), and Peenemünde, Odra lagoon, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (4 861 bp in 2006).

Figure 5: The development of the largest European Cormorant colony on Vistula Spit, Poland, 1986-2009. Data from Przybysz (1997), Mellin et al. (1997), Goc et al. (2005), Goc (2006) and M. Goc & P. Stepniewski (pers. com).

Management actions for Cormorants

Some Baltic countries have initiated management actions to control breeding numbers in areas where Great Cormorants are causing conflicts with other interests such as fishery or protection of Salmon smolts (e.g. Bregnballe et al. 2003, Bregnballe & Eskildsen 2009, Engström 2001). These actions include oiling or pricking of eggs in ground nesting colonies (e.g. up to 18 % of all nests in Denmark and many nests in Sweden) and scaring of birds attempting to found new colonies in hitherto unexploited areas. Furthermore, many countries permit shooting of Cormorants according to the regulations of Article 9 (1) of the Bird Directive). Illegal actions against breeding Great Cormorants are also reported.

Cormorants have been shot since the early- or mid-1990s in Denmark (2 400-5 100 annually), Germany (1 500-2 500 in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Schleswig-Holstein), and Sweden (2 000-8 000). In Estonia, shooting of Cormorants was started in 1997, but the bag remained low in all years, reaching a maximum of 354 in 2006. In Lithuania, in 2005 the Minister for the Environment issued a legal decree which forms the legal basis for licenses for shooting of Cormorants. In Åland, permission to shoot 100 Cormorants was given in 2008.

The total number of Cormorants shot in the Baltic Sea area is in the range of 10 000-20 000 birds annually and should not affect significantly the population development. In Germany, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, culling of young Cormorants just before fledging has been practised from 2001-2005 (a total of 16 000 young being culled), but was stopped afterwards because of strong public protests.

Table 1: Shooting of Cormorants in Denmark, Sweden, the Baltic Federal States of Germany, Estonia and Lithuania.

| Year | Denmark | Sweden | Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania | Schleswig-Holstein | Estonia | Lithuania* | Total |

| 1993 | 1 600 | 232 | 225 | 0 | |||

| 1994 | 2 400 | 191 | 245 | 0 | |||

| 1995 | 3 000 | 321 | 136 | 0 | |||

| 1996 | 3 700 | 675 | 117 | 0 | |||

| 1997 | 4 300 | 748 | 110 | 4 | |||

| 1998 | 3 600 | 1 142 | 626 | 0 | |||

| 1999 | 3 700 | 363 | 677 | 41 | |||

| 2000 | 2 400 | 603 | 681 | 42 | |||

| 2001 | 3 700 | 829 | 610 | 102 | |||

| 2002 | 3 400 | 1011 | 699 | 83 | |||

| 2003 | 3 800 | 9 028 | 1 555 | 777 | 158 | 15 318 | |

| 2004 | 4 900 | 5 702 | 586 | 896 | 127 | 12 211 | |

| 2005 | 3 700 | 3 729 | 881 | 684 | 101 | 2 596 | 11 691 |

| 2006 | 4 400 | 2 157 | 688 | 1 076 | 354 | 1 782 | 10 457 |

| 2007 | 5 100 | 3 504 | 1 245 | 929 | 345 | 761 | 11 884 |

| 2008 | 3 900 | 1 385 | 1 244 | 407 | 484 |

[*] Numbers shot on the basis of the Ministerial Decree on Cormorant Regulation from 2005; shooting permissions are given on annual basis, especially for fish ponds.

Beside shooting, incidental killing of Cormorants in fishing gear is another important anthropogenic mortality factor. Local studies and analyses of ring recovery data indicate that the number of birds drowned in fishing gear maybe high, at least in some regions (Bregnballe 1999, Bregnballe & Frederiksen 2006, I.L.N. & IfAÖ 2005; IfAÖ & I.L.N. 2006).

Metadata

Technical information

Data sources: Population data 2006 have been obtained from the European Cormorant Count organized by the Wetlands International Cormorant Research Group and the "Extended network and conflict analysis project" of COST-INTERCAFE. During this census, counts were nationally coordinated by S. Bzoma, M. Goc, I. Mirowska-Ibron & M. Kalisiński (Poland), H. Engström & R. Staav (Sweden), A.R. Gaginskaya, V. Lilleleht, M. Dagys, G. Grishanov & I. Nigmatoulline (Russia, Estonia, Lithuania), and K. Millers (Latvia).

Annual surveys of the breeding population are organized and data are collected by the following institutions or people[2]:

Denmark: National Environmental Research Institute (NERI), Aarhus University (published on the web site: http://www.dmu.dk)

Germany: Staatliche Vogelschutzwarte Schleswig-Holstein; Agency for Environment, Nature Conservation, and Geology of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

Finland: Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE; published on the web site http://www.environment.fi);

Estonia: Vilju Lilleleht (until 2008), Environmental Board of Estonia in collaboration with K. Rattiste & L. Saks (2009)

Gotland (Sweden): Kjell Larsson

Katy Rybackie (Poland): Michal Goc and Pawel Stepniewski

The numbers of Cormorants shot are available from national hunting reports. Hunting statistics are organized by national authorities in Germany, Denmark, Lithuania, and Estonia. Swedish data have been obtained from the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management.

Geographical coverage: The population data of 2006 (Figure 1) represent a comprehensive census, covering the entire area of the Baltic Sea states.

The population developments shown in Figures 2-4 are representing annual nest counts in representative regions of the Baltic Sea (south-western Baltic: Denmark, Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania; central Baltic: the island Gotland/Sweden, northern and eastern Baltic: Estonia and Finland.

Temporal coverage: see figures and table

Methodology and frequency of data collection: annual nest counts in all colonies in the sample areas (Denmark, Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Gotland, Estonia, Finland); annual nest counts in the Katy Rybackie colony/Poland; Baltic-wide Cormorant count in 2006.

Quality of information

The reliability and quality of data is high.

References

Bregnballe, T. (1996): Udviklingen i bestanden af Mellemskarv i Nord- og Mellemeuropa 1960-1995 (English summary). Dansk Ornitologisk Forenings Tidsskrift 90: 15-20.

Bregnballe, T. (1999): Seasonal and geographical variation in net-entrapment of Danish Great Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis. Dansk Ornitologisk Forenings Tidsskrift 93: 247-254.

Bregnballe, T., Engström, H., Knief, W., van Eerden, M.R., van Rijn, S., & Eskildsen, J. (2003): Development of the breeding population of great cormorants in The Netherlands, Germany, Denmark and Sweden during the 1990s. Die Vogelwelt 124: 15-26.

Bregnballe, T. & J. Eskildsen (2008): Danmarks ynglebestand af skarver i 2008. DMU Report, http://www.dmu.dk

Bregnballe, T. & Eskildsen, J. (2009): Forvaltende indgreb i danske skarvkolonier i Danmark 1994-2008. – Omfang og effekter af oliering af æg, bortskræmning og beskydning. Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser, Aarhus University. Arbejdsrapport fra DMU nr. 249. http://www.dmu.dk/Pub/AR249.pdf

Bregnballe, T. & Frederiksen, M. (2006): Net-entrapment of great cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis in relation to individual age and population size. Wildlife Biology 12: 143-150.

Bregnballe, T. & J. Gregersen (1995): Udviklingen i ynglebestanden af Skarv Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis i Danmark 1938-1994 (English summary). Dansk Ornitologisk Forenings Tidsskrift 89: 119-134.

Engström, H. (2001): The occurrence of the Great cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo in Sweden, with special emphasise on the recent population growth. Ornis Svecica 11: 155-170.

Goc, M.; L. Iliszko & L. Stempniewicz (2005): The largest European colony of the Great Cormorant on the Vistula Spit (N Poland) - an impact on the forest ecosystem. Ecol. Questions 6: 111-122.

Goc, M. (2006): Kormoran w Europie i Polsce: stan populacji, status prawny, regulacja liczebności. In: Wołos A., Niedoszytko B. (eds.) Jeziora Raduńskie: Przemiany i kierunki ochrony. Olszyn. Pages 73-85.

Herrmann, C. (2007): Bestandsentwicklung und Kormoranmanagement in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. BfN-Skripten 204, 48-71.

IfAÖ & I.L.N. (2006): Räumliches und zeitliches Muster der Verluste von See- und Wasservögeln durch die Küstenfischerei in Mecklenburg-Vorpommen und Möglichkeiten zu deren Minderung. Research Report on behalf of the Agency for Environment, Nature Conservation, and Geology MV.

I.L.N. & IfAÖ 2005. Verluste von See- und Wasservögeln durch die Fischerei unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der international bedeutsamen Rast-, Mauser- und Überwinterungsgebiete in den Küstengewässern Mecklenburg-Vorpommerns. Research Report on behalf of the Agency for Environment, Nature Conservation, and Geology MV.

Koop, B. & J.J. Kieckbusch (2007): Ornithologische Begleituntersuchungen zum Kormoran. Report on behalf of the Ministry for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Areas Schleswig-Holstein. Unpublished.

Lehikoinen, A. (2006): Cormorants in the Finnish archipelago. Ornis Fennica 83: 34-46.

Lilleleht, V. (2008): Kormorani levik ja arvukus Eestis. Unpublished Report.

Mellin, M.; I. Mirowska-Ibron; J. Gromadzka & R. Krupa (1997): Recent development of the Cormorant breeding population in north-eastern Poland. Suppl. Ric. Biol. Selvaggina 26: 89-95.

Przybysz, J. (1997): Kormoran [Cormorant]. Lubuski Klub Przyrodników. Świebodzin. 108 pp.

Staav, R. 2007. Storskarven i Sverige. In: SOF 2007. Fågelåret 2006. Stockholm.

SYKE (Finnish Environment Institute, 2008): Breeding population of cormorants now more than 10 000 pairs. Press release, 08/27/2008, http://www.environment.fi

SYKE (Finnish Environment Institute, 2009): Nesting cormorant population grew by one quarter since last year. Press release, 08/03/2008, http://www.environment.fi

Žydelis, R., G. Gražulevičius, J. Zarankaitė, R. Mečionis & M. Mačiulis (2002): Expansion of the Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis) population in western Lithuania. Acta Zoologica Lituanica 12: 283-287.

Van Eerden, M. R. & J. Gregersen (1995): Long-term changes in the northwest European population of Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis. Ardea 83: 61-79.

Footnotes

[1] Numbers include inland colonies; for Germany, only to the Baltic Federal States Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Schleswig Holstein are considered, for Russia St Petersburg and Kaliningrad regions.

[2] Population data from Gotland/Sweden and Katy Rybackie are not obtained from official sources.

For reference purposes, please cite this indicator fact sheet as follows:

[Author’s name(s)], [Year]. [Indicator Fact Sheet title]. HELCOM Indicator Fact Sheets 2009. Online. [Date Viewed], http://www.helcom.fi/environment2/ifs/en_GB/cover/.

Last updated: 12 January 2010