Health Assessment in the Baltic grey seal (Halichoerus grypus)

|

||||

1)Swedish Museum of Natural History, dept. of Contaminant Research, Box 50007, S-104 05 Stockholm. 2)Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute, Turku Game and Fisheries Research, Itäinen Pitkäkatu 3, FIN-20520 Turku. 3)Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira, Fish and Wildlife Health Research Unit, P.O.Box 517, 90101 Oulu, Finland.

Key messages

The reproductive health in investigated grey seals has improved since the middle of 1980s and the population is increasing at about 8% a year since 1990.

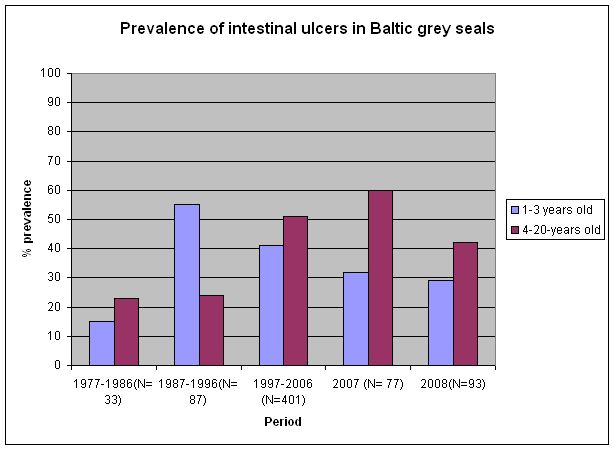

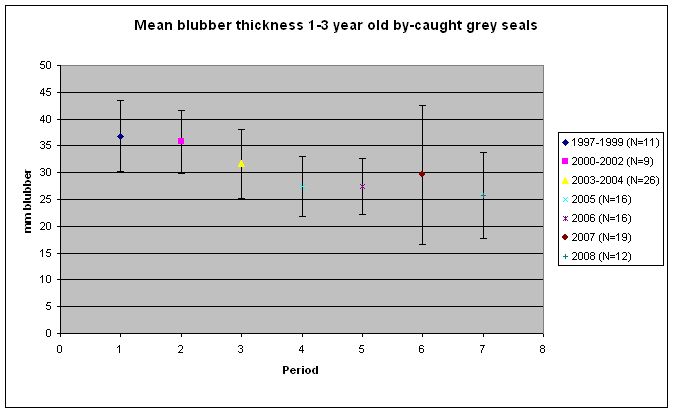

The prevalence of intestinal ulcers has increased significantly in investigated juveniles (1-3 years old) since the middle of 1980s and in adults (4-20 years old) in the 1990s. The mean blubber thickness has decreased significantly in investigated by-caught juveniles during the last 10 years. There is no significant correlation between the prevalence of intestinal ulcers and a thin blubber layer in juveniles.

Results and Assessment

Relevance of the indicator for describing developments in the environment

Grey seals are top predators and fish eating mammals and their health condition reflects the state of the Baltic environment. They are distributed more or less in the entire Baltic Sea, with the largest populations in the southern parts of the Gulf of Bothnia and the northern parts of the Baltic proper. The Baltic grey seals have been suffering from various health defects during the last decades, which have been associated with the deterioration of the general status of the Baltic Sea.

Policy relevance and policy references

The HELCOM recommendation on Conservation of seals in the Baltic area 27-28/2 2006-07-08. In the Baltic Sea Action Plan (adopted 2007-11-15, Poland) where seal health is defined as an indicator of a healthy wildlife in the Hazardous substances segment.

Assessment

The grey seals are assessed on a population level by assessing the population health status. The cause of death and health variables can only be recorded in examined animals and conclusions for the whole population is statistically depending on the number of seals examined. For the interpretations of the results it is important to record the cause of death in examined grey seals.

The population health status can be defined as the sum of the following indicators.

1. Blubber thickness describing the common nutritional state

2. Cause of death in examined seals. This indicator is divided into three classes (hunt, drowning and disease/other cause)

3. Rate of pregnancy describing the reproductive health of the population

4. Rate of fecundity (same as above)

5. Occurrence of uterine pathology (same as above)

6. Occurrence of intestinal ulcers in 1-3 year old seals, is describing an observed pathological change with unknown cause

7. Parasites (species diversity and abundance) describing infection pressure, foraging patterns and Baltic environmental conditions

Common nutritional state

During the last 20 years, the Baltic grey seal population has been increasing at a normal rate, making the conclusion that their nutritional state also has been good in general. Blubber thickness is a commonly used method to describe the nutritional state of marine mammals. The mean sternum blubber thickness has been measured mainly in by-caught seals since 1975. Therefore this site on the seal is used for time trend analysis of blubber thickness. In hunted seals, mainly from the Gulf of Bothnia after 2001, a mean sternum blubber thickness has been measured and calculated from April to December and the mean blubber thickness exceeds 30 mm in all months for both sexes and age classes.

In general, the blubber thickness has remained above 30 mm in most Baltic grey seals since the 1980s. On the other hand, the mean blubber thickness has decreased significantly over the last 10 years in 1- to 3-year-old bycaught grey seals (Fig. 4). The reason for the observed change is not known.

Human impact on seal population size

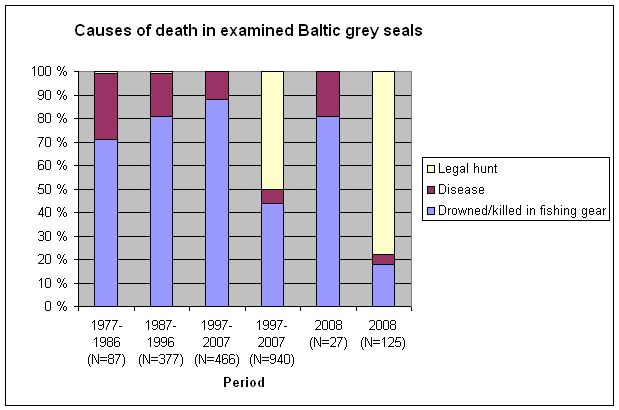

Since 1999 in Finland and 2001 in Sweden, grey seals have been legally hunted. Currently, annual quotas are about 1000 in Finland (including Åland) and 180-210 in Sweden and about 50% of quota is used (Anon. 2007). Another important human-related cause of death is drowning in fishing gear. Estimating the amount of by-catch is difficult because fishermen are not obliged to report by-catches. Environmental pollution caused by human activities has been linked to reproductive failures in grey seals, but during the last decade reproduction has normalized. The most common cause of death of the examined grey seals is hunt (after 2001) and drowning in fishing gear (Fig.5).

Reproductive health

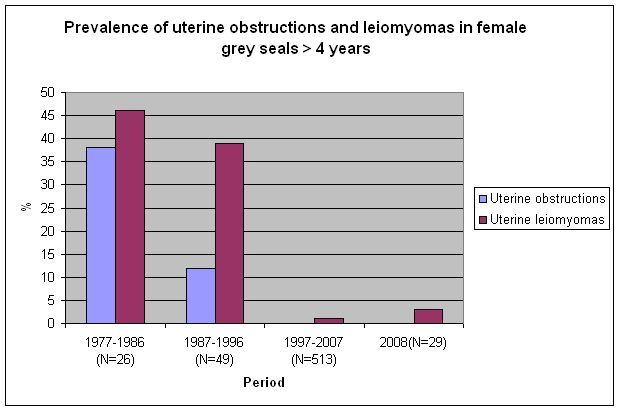

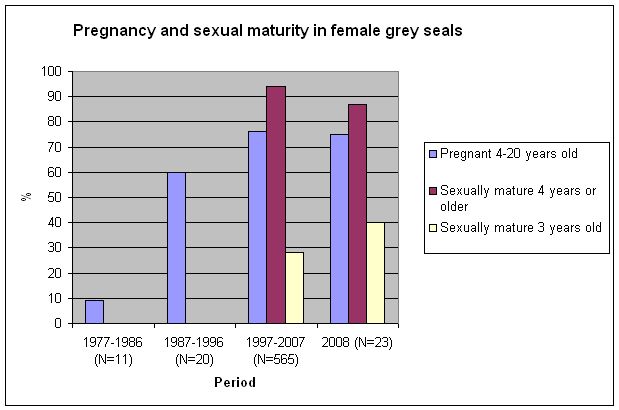

The health status in wild populations is commonly assessed by the reproductivity of the females, and the proportion of pups in the population. The reproductive health of the Baltic grey seal population has been assessed as the prevalence of uterine obstructions and uterine tumours (leiomyomas) (Fig.1), pregnancies after the implantation period and ovulation in seals at age 4-20, and by the prevalence of sexual maturity in 3 years old (Fig.2). Obstructions by narrowing (stenosis) and closure (occlusion) of the uterine lumen were earlier common in Baltic grey seals older than six years (Bergman and Olsson 1985). Remnants of foetal membranes have been found associated with these lesions as signs of abortion (Bergman and Olsson 1985). These uterine disorders can prevent or impede pregnancies. Uterine leiomyomas have been common in female grey seals above 22 years of age. These benign smooth muscle cell tumours are mostly localised in the wall of the uterine corpus. They are often multiple and sometimes up to 10 cm in diameter (Bergman and Olsson 1985, Bergman 1999; Bäcklin et al. 2003). These tumours, depending on localisation, may make pregnancy more difficult to take place. There are also indications that PCB is involved in uterine leiomyoma development and/or growth (Bredhult et al., 2008). Trends in percent of sexual maturity (ovulation) in 3 years old females and ovulation in 4-years or older females are interpreted as a signs of normal seasonal reproduction. It is defined by the presence of a corpus luteum in the ovaries.

The results show that the Baltic grey seal fertility has improved markedly during the last decades. The improvement was significant regarding the decreased prevalence of uterine obstructions and the increased number of pregnant animals. Ovulation was recorded in almost all (94 %) examined females, 4 years or older in 1997-2007. Among the 3 years old females 28 % were sexually mature in the same period.

Intestinal ulcers

From the middle of 1980s the prevalence of intestinal ulcers, mostly localized in the ileum-caecum-colon region, in 1- to 3-year-old grey seals increased significantly compared to the decade before. Thereafter (1987-2008), the prevalence decreased slightly, but is still high (Fig. 3). Several years after the increase in young seals, there was a significant increase in 4-20 years old grey seals. These results indicate that the ulcers observed in adult seals started to develop earlier in life.

Early intestinal lesions show solitary or multiple, often confluent areas with slight denudation of the epithelium surrounded by Acanthocephalans (Corynosoma sp.). Often the muscular tunic of the diseased part of the intestine is thickened. The size of the ulcers may vary from a few millimetres in diameter to extended ones encompassing large parts of ileum and colon. If the ulcerous process reaches the muscular tunic the serosa may show chronic inflammation with fibrinous or fibrous adherences between the intestinal portions and closely situated abdominal organs. At this stage perforation of the intestinal wall is common. Death from colonic ulcer occurs at all ages, from one-year-olds (Bergman and Olsson 1985, Bergman 1999). The prevalence of colonic ulcers of moderate and severe degree i.e. lesions exceeding 10 mm in diameters is the only ones that are considered (Bergman, 1999). The high prevalence of intestinal ulcers seems unique for the Baltic population of grey seals. Examination of grey seal intestines from the Scottish east coast and Atlantic coast of Ireland, revealed no signs of ulcers (Bergman, 1999; O´Neill and Whelan, 2002). In Atlantic grey seals Acantocephala (Corynosoma sp.) may create very small lesions in the intestinal mucous membrane but only one case of intestinal ulcer in grey seals has been reported outside the Baltic Sea (Baker 1980;1987). The high prevalence of ulcers of moderate to severe degree in the young Baltic grey seal indicates an impaired or delayed healing process, which may involve the immune- as well as the hormonal system.

Parasites

Grey seals harbour several species of parasites. Monitoring prevalence of parasite species indicates species of fish consumed and the resistance in the seals for parasite infections. Parasites found in Baltic grey seals are listed in Table 1. Beside parasites listed, there have been some findings of larval stages of Cestoda (Schistocephalus solidus and Diphyllobothrium sp.) in grey seal intestines (Helle and Valtonen, unpublished data). The final hosts for S. solidus are fish-eating birds and rodents and it has no adult stadium or effect on the grey seal. Grey seals get it by eating the three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). Some species of Diphyllobothrium may have seals as final hosts but adult stages of this tapeworm haven’t been found. There have also been findings of Porrocaecum sp. (or Pseudoterranova decipiens) in the stomach and intestines and Anisakis sp. in the stomach (Bergman, 2007). Data on parasite abundance is not available in database yet.

Table 1. Baltic grey seal endoparasites

| Parasite species | Location in seals | Location in Baltic Sea | References |

NEMATODA Contracaecum osculatum |

Stomach |

Bothnian Bay |

Valtonen et. al, 1988 |

ACANTHOCEPHALA Corynosoma semerme Corynosoma magdaleni Corynosoma strumosum |

posterior parts of intestine small intestine small intestine |

Gulf of Bothnia |

Nickol et. al, 2002 |

TREMATODE Pseudamphistomum truncatum |

Liver |

not specified |

Bergman, 2007 |

Data

Figure 1. Prevalence of uterine obstructions and uterine leiomyomas in by-caught/stranded and hunted examined grey seals older than 4 years in Sweden and Finland. The decreased prevalence of uterine obstructions is significant (p<0.05). N is the number of investigated animals. The prevalence of leiomyomas in the last decade is uncertain since the number of examined seals, above 22 years of age, has decreased since 1996.

Figure 2. The prevalence of pregnant 4-20 years old, and sexually mature 3 years old, and 4 years or older examined females in Sweden and Finland. Only animals found after the implantation period (August to February) are included in the pregnancy investigation. The increase in pregnancies between the first two decades (1977-1986 and 1987-1996) is significant (p<0.05). Sexual maturity data from 1977 to 1996 is not available in yet.

Figure 3. The prevalence of intestinal ulcers in examined juvenile and adult grey seals in Sweden. The increased prevalence in 1-3 years old between the first two decades is significant as well as the increase later in 4-20 years old (p<0.05). N is the number of investigated animals.

Figure 4. The mean blubber thickness ± SD in examined 1-3 years old by-caught grey seals from 1997 to 2008 in Sweden. The decrease in mean blubber thickness since 1997 is significant (p<0.001). Usually the blubber layer in the Baltic grey seal is thicker in the second half of the year compared to the first half. In 1997-1999, 54% of the examined animals were found in fishing gear in the second half of the year (July-December) and in 2000-2008, more than 93%. N is the number of investigated animals.

Figure 5. Causes of death in examined Baltic grey seals in Sweden and Finland. The period 1997-2007 and 2008 is presented with hunt included and excluded. N is the number of investigated animals.

Metadata

Technical information

Data source: The National Swedish Monitoring Program of Seas and Coastal areas, Swedish EPA, Swedish Museum of Natural History. Baltic grey seal necropsy data of Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute and Finnish Food Safety Authority, years 1977-2002. Baltic grey seal necropsy data of Finnish Food Safety Authority years, 2002-2008. Baltic grey seal reproduction health data of Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute, years 2000-2007.

Description of data: Necropsy of by-catch, hunted and stranded grey seals, sample preparation and evaluation of results has been carried out by the dept. of Contaminant Research at the Swedish Museum of Natural History and by Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute and/or Finnish Food Safety Authority.

Geographical coverage: The Swedish and the Finnish coast of the Baltic Sea

Temporal coverage: see figures.

Methodology and frequency of data collection: see Bergman (1999)

Methodology of data manipulation: For statistical evaluation two tailed Fishers exact test or t-test were used.

Quality information

Sweden: During these three decades two persons (veterinarian and patho-biologist) have performed the necropsies, the first one between 1977 and 2002. Finland: During these three decades several persons (veterinarians, seal biologists) have performed the necropsies.

National consultations and synchronisations are made continuously between persons. Age determinations of the grey seals are performed by counting growth layer groups (GLGs) in the cementum of teeth according to a well established method. Readings of tooth sections are made independently by two persons.

References

Anon. 2007. Management plan for the Finnish seal populations in the Baltic Sea. Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry 4B:95 pp.

Baker, J.R. 1980. The pathology of the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus ). II. Juveniles and adults. British Veterinary Journal 136, 443–447.

Baker J.R. 1987. Causes of mortality and morbidity in wild juvenile and adult grey seals (Halichoerus grypus). Br. Vet. J. 143: 203-220.

Bergman A. and Olsson M. 1985. Pathology of Baltic grey seal and ringed seal females with special reference to adrenocortical hyperplasia: Is environmental pollution the cause of a widely distributed disease syndrome? Finn Game Res 44:47-62.

Bergman A. 1999. Health condition of the Baltic grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) during two decades. APMIS 107:270-82.

Bergman A. 2007. Pathological changes in seals in Swedish waters: The relation to environmental pollution. Tendencies during a 25-year period. Thesis No.2007:131, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, ISBN 978-91-85913-30-5.

Bredhult C, Bäcklin B, Bignert A and Olovsson M. 2008. Study of the relation between the incidence of uterine leiomyomas and the concentrations of PCB and DDT in Baltic gray seals. Reproductive Toxicology25 (2):247-225.

Bäcklin, B., Eriksson L., and Olovsson M. 2003. Histology of uterine leiomyoma and occurrence in relation to reproductive activity in the Baltic gray seal Halichoerus grypus. Vet. Pathol. 40:175-180.

O’Neill G and Whelan J. 2002. The occurrence of Corynosoma strumosum in the grey seal, Halichoerus grypus, caught off the Atlantic coast of Ireland. Journal of Helminthology, 76, 231–234.

Nickol, BB, Helle E and Valtonen ET 2002. Corynosoma magdaleni in gray seals from the Gulf of Bothnia, with emended descriptions of Corynosoma strumosum and Corynosoma magdaleni. J. Parasitol. 88(6), 1222-1229.

Valtonen, ET, Fagerholm, HP and Helle E 1988. Contracaecum osculatum (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in fish and seals in Bothnian Bay (Northeastern Baltic Sea). Int. J. Parasitol. 18(3): 365-370.

For reference purposes, please cite this indicator fact sheet as follows:

[Author’s name(s)], [Year]. [Indicator Fact Sheet title]. HELCOM Indicator Fact Sheets 2009. Online. [Date Viewed], http://www.helcom.fi/environment2/ifs/en_GB/cover/.

Last updated: 30 September 2009